Author: Munehisa

Compiled by: Vernacular Blockchain

Executive Summary

- Throughout history, money has evolved around three core functions: as a medium of exchange, a store of value, and a unit of account. Simultaneously, the pursuit of faster settlement, lower costs, and borderless use has driven the transformation of money from localized barter systems to today's global digital networks.

- Since the end of World War II, the US dollar has become the world's dominant currency, fulfilling the key attributes of money more effectively than any other currency.

- Stablecoins represent the next stage in the evolution of money and payments systems, laying the foundation for the financial system with faster settlement, lower fees, seamless cross-border functionality, native programmability, and a strong audit trail. Today's stablecoin ecosystem includes several different types of stablecoins, primarily distinguished by their collateral backing, degree of decentralization, and the mechanisms used to maintain their price peg.

- USD-pegged stablecoins are in high demand due to their multiple use cases, including: store of value, cross-border remittances, payments, yield generation, cryptocurrency trading, and as a shadow monetary policy tool.

- Stablecoins are becoming a powerful tool for shadow monetary policy and are increasingly viewed by governments and finance departments as a strategic tool for managing sovereign debt and promoting the influence of monetary and financial systems.

- We estimate that the total market capitalization of stablecoins will reach approximately $4.9 trillion over the next decade, a nearly 20-fold increase from current levels.

introduction

Below, we provide a brief historical overview of currency, the US dollar, and central banks. If you'd like to jump straight into the world of stablecoins, skip to the "Stablecoins" section.

In the aftermath of the global financial crisis and its subsequent government bailouts of overleveraged financial institutions ("Chancellor on the verge of a second bailout for banks"), Bitcoin emerged as a non-sovereign alternative, aiming to achieve "a purely peer-to-peer form of electronic cash, allowing online payments to be sent directly from one party to another without going through a financial institution." While Bitcoin has successfully served as a censorship-resistant, owner-operated asset independent of any central authority, limitations such as low transaction throughput, slow settlement times, high fees, high price volatility, and a poor user experience have prevented it from becoming a practical tool for everyday payments. While Bitcoin may ultimately prove to be a superior form of money (capable of withstanding the debasement of fiat currencies and the arbitrary decisions of central bankers), the vast majority of global trade currently remains conducted in US dollars. Stablecoins, digital representations of the US dollar, are increasingly taking over the role of the electronic cash system originally envisioned by Bitcoin.

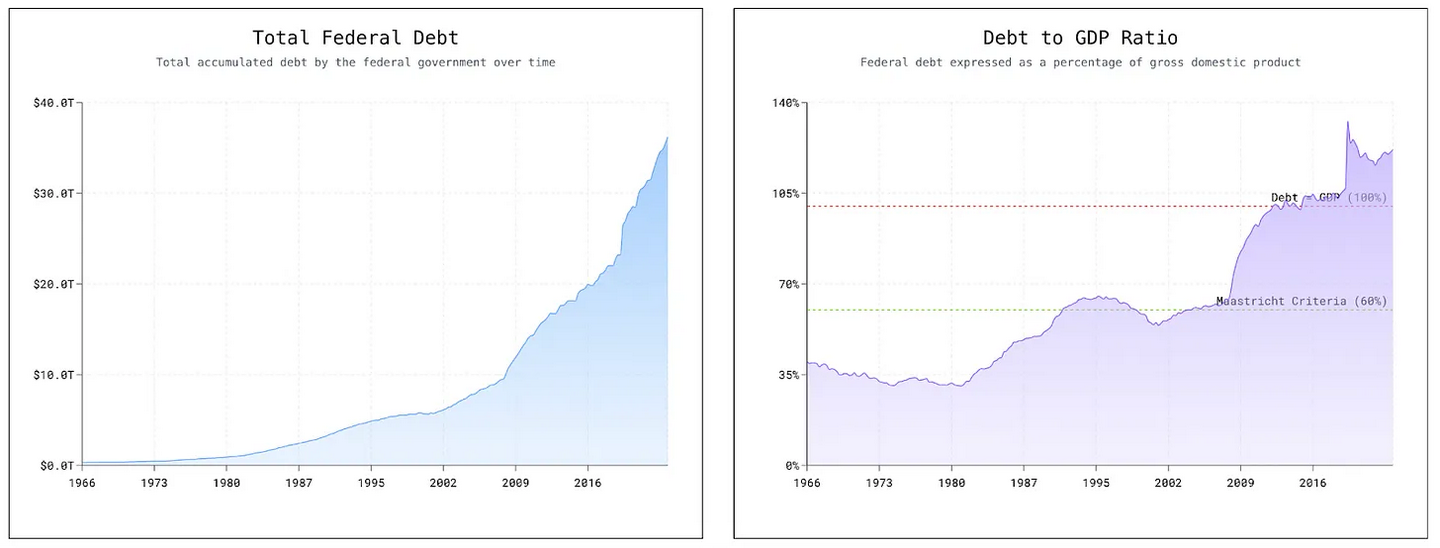

These "room-temperature superconductors of financial services" are revolutionizing value transfer for individuals in hyperinflationary or authoritarian regimes, enabling low-cost peer-to-peer remittances and payments, while also improving user experience and real-time functionality for multinational corporations. Furthermore, we believe that the structural debt dynamics of the United States, the need to find new marginal buyers of U.S. Treasury bonds, the need to maintain the dollar's hegemony, and the Trump administration's deregulatory stance and macroeconomic policies are laying the foundation for a long-term bull market in stablecoin adoption. Against this backdrop, we expect the total circulating market capitalization of stablecoins to expand into the trillions of dollars.

History of Currency

To understand why stablecoins represent the future of money and settlement, we first need to trace the historical evolution of money and identify the core attributes that enable monetary systems to effectively serve society. This includes not only the macro-trajectory of monetary development, but also the rise of the US dollar hegemony and the "exorbitant privilege" enjoyed by the United States as the issuer of the world's dominant reserve currency.

Barter and Commodity Money

Early civilizations relied on barter, the direct exchange of goods and services. As social complexity grew, barter became inefficient, leading to the emergence of commodity currencies such as livestock (9000-6000 BC) and cowrie shells (circa 1200 BC in Asia). These early currencies had intrinsic or socially recognized value, laying the foundation for standardized media of exchange.

Metal currency

As trade networks expanded, societies gradually adopted metal as a medium of exchange due to its durability and ease of divisibility. During the Zhou Dynasty in China (circa 1000 BC), metal currency appeared in the form of small bronze tools and cast shell imitations. By the 7th century BC, India, China, and the Aegean region had independently developed true currency. Indian currency consisted of punched metal disks, while Chinese currency consisted of cast bronze coins, often with holes for easy stringing. In Anatolia, the Kingdom of Lydia introduced the first standardized currency, using seals to verify its metal content. This innovation marked the unification of currency's functions as a store of value and a medium of exchange, while allowing the state to regulate the money supply and profit from seigniorage. The shift from commodity barter to metal currency significantly expanded long-distance trade. For example, Athenian silver coins financed imperial expansion and widespread circulation, while Chinese bronze coins helped unify the East Asian market.

Paper Money and Credit

While metal money dominated the classical era, medieval China experienced its next major leap forward: the advent of paper money. During the Tang Dynasty (618-907), merchants used promissory notes in the form of "flying money" to avoid transporting heavy copper coins over long distances. This system evolved into formal paper currency during the Song and Yuan dynasties, preempting the use of paper money in China by 500 years. However, excessive issuance led to inflation, and by 1455, the Ming Dynasty abandoned paper money due to severe devaluation. Although paper money did not arrive in Europe until centuries later, China's experience highlights the efficiency and risks of similar fiat currencies. Meanwhile, in 12th-century England, the Royal Exchequer used notched wooden tally sticks to record debts and taxes as a form of credit money. These tally sticks circulated as "bookkeeping money" for transactions with the crown and remained in use until the 19th century. These innovations marked the transition of money toward abstract forms—written instruments and credit records—laying the foundation for modern banking.

Banknotes, Trading Platforms, and Central Banks

By the late Middle Ages and Renaissance (15th-17th centuries), formal banking and the first paper money emerged in Europe. Wealthy families like the Medici family of Florence operated banks, holding deposits and extending credit. They pioneered double-entry bookkeeping, laying the foundation for modern financial accounting. In the 16th century, Antwerp and Amsterdam became financial centers, with bills of exchange, marine insurance, and international credit supporting expanding global trade. The creation of public banks was a major breakthrough. The Bank of Amsterdam, founded in 1609, accepted various currencies and issued certificates of deposit, creating a stable ledger currency, or "bank money," which was widely used in European trade. Merchants could transfer balances directly between bank accounts, foreshadowing modern checking accounts. Paper money made its European debut in the 17th century. In 1661, the Bank of Stockholm, Sweden, issued the first public paper money, backed by deposits of heavy copper plates. Despite initial success, over-issuance led to the bank's collapse in 1664. In 1694, the Bank of England was established and began issuing banknotes, receipts for deposits and government loans. These early notes represented currency, redeemable for gold and silver. Over time, the Bank of England acquired a monopoly on note issuance, marking a pivotal shift from a private to a centralized, state-owned monetary system. This period marked the rise of central banks and national currencies.

Fiat Tender vs. National Currency

By the 18th century, paper money and banknotes were ubiquitous in Western economies, though not always stable. During the American Revolutionary War and the French Revolution, governments issued paper money that was not fully backed by metal—an early form of legal tender. The "Continental Dollars" issued by the Continental Congress quickly depreciated due to excessive issuance, leading to the saying "not worth a single Continental Dollar." In the 19th century, national currencies began to take on their modern form. Many countries established central banks or treasuries to issue standardized notes and currency. Peacetime metal-backed banknotes became the norm, restoring public trust. In the United Kingdom, the Bank Charter Act of 1844 required Bank of England notes to be backed by gold, making them the dominant legal tender. Other countries followed suit, pegging their currencies to precious metals to enhance their credibility. This marked the beginning of the gold standard era.

Gold Standard

The 19th century saw a heated debate over whether currency should be based on gold, silver, or both. At the beginning of the century, many countries adopted a bimetallic standard, treating both gold and silver as legal tender. For example, the US Currency Act of 1792 established a silver-to-gold ratio of 15:1 by weight. However, as global trade grew and new metals became available, fluctuations in relative value led to one metal crowding out the other—an example of Gresham's Law. Britain was the first to move to a pure gold standard in 1816, defining the pound solely in gold and ceasing the minting of high-value silver coins. By the end of the 19th century, other major economies had followed suit, and gold became the dominant standard for international trade. The bimetallic debate was particularly intense in the United States. After the discovery of large quantities of silver depreciated its value, the "Sin of '73" Act of 1873 ended the minting of silver dollars, propelling the United States onto a de facto gold standard. Despite strong populist pressure to restore silver, gold supporters ultimately prevailed. The Gold Standard Act of 1900 formally defined the dollar as approximately 1/20.67 ounce of gold, solidifying the United States' commitment to the gold standard monetary system.

Modern Central Banks and Global Institutions

To manage national currencies and ensure financial stability, countries increasingly relied on central banks. Early examples include Sweden's Riksbank (1668) and the Bank of England (1694). More central banks were established in the 19th and early 20th centuries, including the Bank of France (1800), the German Reichsbank (1876), and the Bank of Japan (1882). In the United States, the Federal Reserve System was created in 1913 to respond to recurring bank panics and regulate credit. Under the gold standard, central banks were typically granted the exclusive right to issue banknotes. For example, the Bank of England became the sole legal issuer in the mid-19th century, and the Federal Reserve System assumed this role after 1913. Central banks also managed gold reserves and maintained fixed exchange rates, with ensuring the convertibility of banknotes into gold being a core responsibility. However, during World War I (1914-1918), many countries suspended gold convertibility to finance war spending through money printing. The United States also suspended gold convertibility for domestic transactions in 1933 during the Great Depression.

electronic money

The form of money has evolved continuously with technological advancements. In the mid-20th century, banks began using computers, paving the way for electronic money transfers. By the 1970s, the SWIFT system enabled instant global movement of funds via electronic signals, eliminating the need for physical cash. At the consumer level, payment cards transformed how people access money, starting with the Diners Club card in the 1950s and culminating in the widespread adoption of credit and debit cards in the 1960s and 1970s. By the end of the 20th century, most money existed as digital ledger entries, not paper bills. The internet accelerated this shift. By the 1990s and 2000s, online banking and platforms like PayPal enabled anyone to send money electronically. The 2010s saw a surge in innovation in mobile payments and fintech, from Kenya's M-Pesa to apps like Alipay and Venmo. Today, in developed economies, most money is fully digital, with physical cash comprising only a small fraction of the total money supply.

Throughout history and civilizations, money has evolved independently around a set of fundamental characteristics that enable it to effectively serve as a medium of exchange, store of value, and unit of account. These properties include:

Fungibility : Each unit of currency must be interchangeable with other units of the same denomination. For example, a $100 bill is functionally identical to any other $100 bill, ensuring uniformity of value and eliminating the need to distinguish between individual units.

Durability : Currency must be able to withstand long-term physical wear and tear. It should retain its shape and function after repeated use and transactions, ensuring long-term circulation.

Portability : To be effective, money must be easy to transport and use across distances. Whether physical or digital, it must be able to be transferred efficiently between parties without excessive friction or cost.

Divisibility : The currency must be easily divisible into smaller units to facilitate transactions of varying sizes.

Uniformity : All banknotes of the same denomination should have identical appearance and value. Standardization enhances trust, simplifies identification, and reduces transaction errors.

Scarcity : To maintain purchasing power, money must exist in a finite supply. If the supply grows too quickly relative to demand, the value of the currency will shrink, leading to inflation and a breakdown of trust.

Acceptability : The currency must be widely recognized and accepted as a valid form of payment. Broad social and institutional acceptance is the foundation of its utility and legitimacy.

Over time, the nature of money has evolved in the pursuit of greater efficiency. People have consistently sought to develop forms of money that are faster to settle transactions, cheaper to circulate, and not restricted by geography, moving from localized barter systems to global digital networks.

US dollar hegemony

The United States has not always enjoyed the privilege of issuing the world's reserve currency, nor has its financial system always been the most dominant, centralized, and legal tender-based, with the deepest and most investable capital markets in the world. The rise of the US dollar has been accompanied by a long struggle to establish a national currency and a central bank. In fact, the evolution of the US currency bears striking similarities to the current stablecoin ecosystem, from the circulation of banknotes in the National Banking Era to the rise, regulation, and controversy of money market funds (MMFs).

We will briefly explore the historical context of the US dollar’s rise to global dominance, which provides important perspective for understanding the long-term tailwinds supporting stablecoin adoption. In our view, understanding stablecoins requires more than just a technical perspective; their trajectory is equally shaped by political and economic forces.

The History of the U.S. Banking System and the Dollar

Hamilton's Blueprint (1775-1791)

Before the establishment of a formal banking system, the American Revolutionary War and the Confederation plunged the nation into financial chaos. The wars were financed with Continental currency, a paper currency that rapidly depreciated, leading to the saying "not worth a single Continental." To restore order, President George Washington appointed Alexander Hamilton as the first Secretary of the Treasury. Hamilton proposed that the federal government assume state debts, issue federal bonds, and create a national bank to regulate money and credit. Disturbed by the chaotic competition among state currencies, Hamilton persuaded Congress to charter the First Bank of the United States, calling it "a political machine of vital importance to the nation" and the key to a unified republic's financial system.

First Banking Era (1791-1811)

In 1791, Congress chartered the First Bank of the United States, signed by President Washington, making it the de facto first central bank of the United States. Headquartered in Philadelphia, with a capitalization of $10 million, 20% held by the government and 80% privately, the bank served as the fiscal agent of the federal government, managing deposits, taxation, payments, and issuing nationally accepted gold and silver-backed paper money. Under President Thomas Willing, the bank opened branches in major cities, stabilizing the postwar economy. However, the establishment of the bank sparked strong opposition from Jefferson and Madison, who considered it unconstitutional and elitist. Although the bank operated effectively, political resistance grew, and in 1811, Congress narrowly voted to deny the renewal of its charter. Without a central bank, the United States faced financial chaos during the War of 1812, highlighting the need for a new national institution and laying the foundation for the establishment of the Second Bank of the United States.

The Second Bank and Jackson's "Bank War" (1816-1836)

In response to the financial chaos following the War of 1812, Congress chartered the Second Bank of the United States in 1816 for a 20-year term, with $35 million in capital and headquarters in Philadelphia. Even President James Madison, who had previously opposed the First Bank, recognized the need for a central financial institution to stabilize the postwar economy. Under the leadership of Nicholas Biddle, the Second Bank focused on regulating credit and the money supply. However, it became a target of President Andrew Jackson's populist campaign against the concentration of financial power. Calling the bank a "nest of vipers and thieves," Jackson vetoed its charter renewal and withdrew federal deposits, effectively destroying the institution.

Free Banking and "Wildcat Money" (1837-1862)

From the late 1830s until the Civil War, during the period known as the Free Banking Era, banking was under state control and lacked federal regulation after the collapse of the Second Bank. States like New York passed "free banking" laws, allowing nearly anyone to open a bank as long as they met basic requirements and provided bond collateral. Without federal oversight, over 8,000 different banknotes circulated, each trading at a discount based on the creditworthiness of the issuing bank and the distance to redemption. Some institutions, known as "wildcat banks," operated in remote areas to avoid redemption and issued notes that were not fully backed by gold or silver, leading to widespread instability and fraud. In states like Michigan, bank failures became commonplace, and the panics of 1837 and 1857 reinforced the public's desire for a national banking framework and a unified currency.

Civil War Financing and the National Bank Act (1863-1879)

The Civil War sparked a financial revolution, as the federal government rushed to finance the war effort. Initially relying on bond sales and tax increases, the North quickly faced a cash shortage, suspending gold and silver convertibility in late 1861 and eliminating currency from circulation. In 1862, Congress passed the Legal Tender Act, authorizing the issuance of $150 million in paper money called "greenbacks." These non-interest-paying Treasury notes were designated as legal tender but not backed by gold. These legal tender notes filled a critical monetary gap, although their discount to gold fueled inflation. Ultimately, approximately $450 million in greenbacks were issued, making this the first large-scale legal tender in American history, a system that continued in use well into the 20th century. While this system brought stability and financed victory, it also triggered significant inflation, with prices in the North rising by approximately 80% during the war. After 1865, efforts shifted toward returning to the gold standard, culminating in the restoration of gold-silver convertibility in 1879 at a fixed rate of $20.67 per ounce.

Gold, Populism, and Morgan's Midnight Rescue (1879-1907)

With the successful restoration of gold and silver payments in 1879, the United States officially entered the era of the classic gold standard, with the dollar pegged to gold at $20.67 per ounce. Greenbacks, gold certificates, and national banknotes were freely convertible into gold. From 1880 to 1914, this period saw strong economic growth and rapid industrialization, culminating in the United States' rise to global economic power. However, repeated banking panics (1884, 1890, 1893, and 1907) highlighted deep structural flaws in the financial system. During these crises, credit and money dried up, interest rates soared, and banks hoarded reserves, leading to a contraction in lending. Clearinghouse associations in major cities attempted to contain losses by issuing emergency loan certificates, but these temporary measures highlighted the lack of a formal mechanism for injecting liquidity. Monetary policy debate intensified, as farmers and debtors in the West and South, driven by gold-induced deflation and falling agricultural prices, demanded the free coinage of silver to expand the money supply. The panic of 1907 forced financier J.P. Morgan to personally organize a private sector rescue, locking up the head of the New York Trust Company until a bailout was reached. This event ultimately catalyzed the creation of the Federal Reserve System.

From Jekyll Island to the Federal Reserve System (1907-1913)

In 1910, Senator Nelson Aldrich secretly convened five prominent financiers on Jekyll Island to devise a plan for a new central bank under pseudonyms, a plan Paul Warburg jokingly described as "as secret as the Confederate Navy." The result was the Aldrich Plan, which proposed a central institution with regional branches, a flexible currency backed by commercial paper and gold, and banker-dominated governance. By 1912, Aldrich had unveiled the plan, but the political tide had shifted: Democrats, long skeptical of concentrated financial power, had won the White House and Congress with the election of Woodrow Wilson. The Aldrich Plan was thwarted by its overly pro-Wall Street stance and its clandestine origins. However, its core concept was retained. Wilson conceded that the plan was "60-70 percent correct." Democrats, led by Representative Carter Glass and Senator Robert Owen, reworked the proposal, and after intense debate, Wilson finalized it. On December 23, 1913, the Federal Reserve Act was signed into law, establishing the Federal Reserve System. Twelve regional "bankers' banks" were authorized to issue flexible Federal Reserve notes and manage the national monetary system.

The Early Years of the Federal Reserve and the Roaring Twenties (1914-1928)

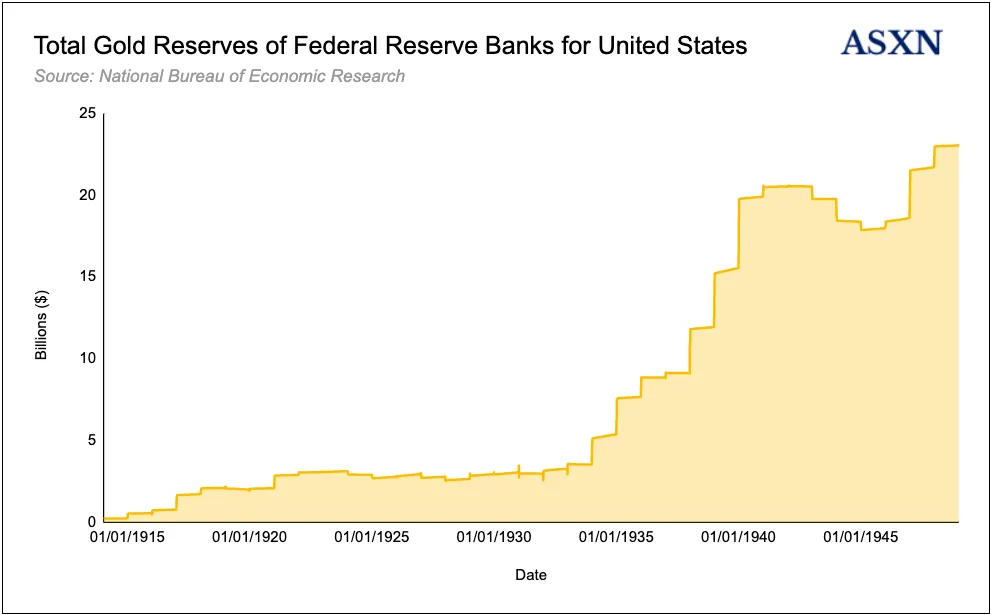

The Federal Reserve System began operating at the outbreak of World War I (1914-1918). Although the United States remained neutral until 1917, the war had an immediate economic impact. Capital flowed into the United States from war-torn Europe, and the United States became the primary supplier of weapons and supplies to the Allied forces, primarily financed through massive loans. New York's financial markets expanded rapidly, and the US dollar began to replace the British pound in international transactions. While many belligerent nations suspended the gold standard to print money to finance the war, the United States remained on the gold standard, leading to a surge in gold inflows. By 1917, the United States held approximately one-third of global central bank and treasury reserves (approximately 11,000-12,000 tons). By the 1920s, the US share of reserves had risen to approximately 40%. At the war's end, the United States became the world's largest creditor, financing the majority of Allied war expenses and shifting the center of global finance from London to New York. By the mid-1920s, the US dollar had become a strong rival to the British pound as a reserve and loan currency. However, imbalances grew: the United States accumulated large gold reserves and actively lent abroad, while much of Europe remained mired in post-war debt and economic fragility.

The Great Depression and the New Deal (1929-1945)

In October 1929, a long-accumulated stock market bubble burst, triggering the Wall Street Crash, wiping out billions of dollars in wealth. The collapse destroyed confidence and rippled through the banking system, with many institutions failing due to exposure to stock loans or securities subsidiaries. Nearly 9,000 banks (roughly one-third of all US banks) failed, and the Federal Reserve failed to act decisively. Its decentralized structure led to internal divisions, prioritizing the preservation of the gold standard over the expansion of credit. Some officials adopted a "liquidationist" stance, arguing that weak banks and borrowers should be allowed to fail. The result was a one-third contraction in the money supply, triggering deflation, a halving of GDP, and a 25% unemployment rate. President Roosevelt declared a banking holiday, passed the Glass-Steagall Act, created the FDIC, and separated commercial and investment banks. Through Executive Order 6102, Americans were forced to surrender gold at $20.67 per ounce in exchange for dollars, effectively nationalizing the metal to prevent a run on the dollar and achieve monetary expansion. The Gold Reserve Act of 1934 confirmed this, devaluing the dollar and driving the price of gold to $35 per ounce. With most of the world's gold and a stable banking system, the US dollar became the dominant currency, laying the foundation for the post-war global monetary order.

Bretton Woods System (1944-1971)

After World War II, the United States emerged with unparalleled economic dominance, producing half of global output and holding approximately 70% of official gold reserves. This position placed it in a unique position to rebuild the international monetary system. The British pound was weakened by massive war debts and a shortage of US dollars, leading many countries to implement currency controls. Drawing lessons from the failures of devaluations after World War I and in the 1930s, the 44 Allied powers established a new framework at the Bretton Woods Conference in July 1944. Led by US Treasury official Harry Dexter White and British economist John Maynard Keynes, the delegates created the Bretton Woods system, establishing the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank and fixing the exchange rate at which the dollar was convertible into gold. This system effectively established the dollar's central role in global finance, underpinned by US economic strength and gold reserves. This position, later known as the "excess privilege," enabled the United States to borrow freely and run external deficits. For the next quarter century, the Bretton Woods system defined international finance until its collapse ushered in the era of the fiat dollar.

The Nixon Shock and the Petrodollar (1971-early 1980s)

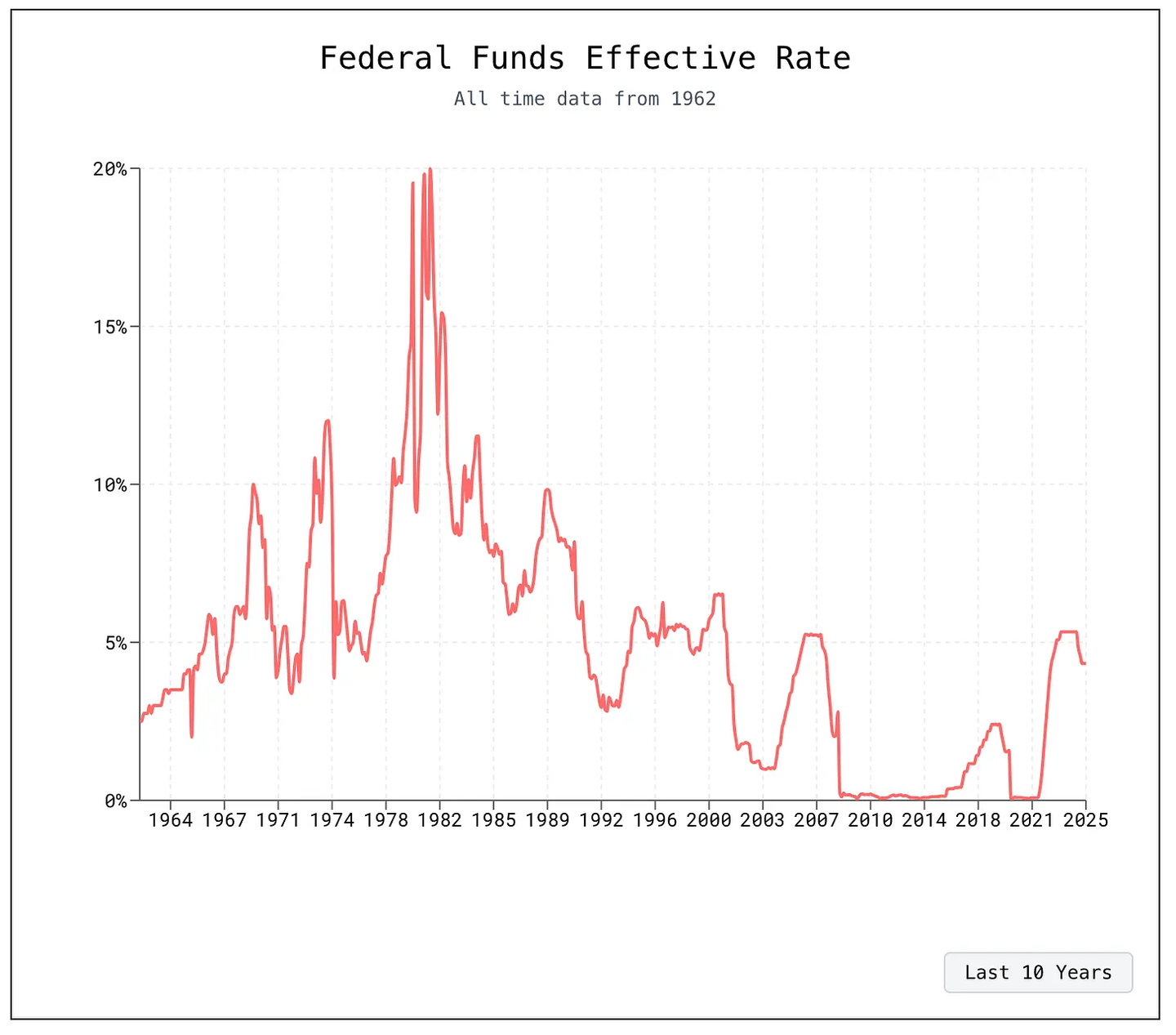

On August 15, 1971, President Nixon unilaterally suspended the convertibility of the US dollar into gold, ending the Bretton Woods system and severing the dollar's last remaining link to gold. This marked a shift to a fiat currency system, with the US dollar and other major currencies floating freely, their value determined by market forces. Despite losing its gold backing, the US dollar retained and expanded its status as a global reserve currency due to a lack of alternatives and continued confidence in US financial markets. After the 1973-74 oil crisis, OPEC significantly raised oil prices, forcing importing countries to obtain more US dollars to pay for energy. In 1974, the United States reached a strategic agreement with Saudi Arabia: military protection and weapons in exchange for Saudi Arabia pricing oil in US dollars and investing its oil revenues in US Treasury bonds. This arrangement was quickly copied by other OPEC members, establishing the petrodollar system. Oil-exporting countries accumulated large US dollar surpluses, which were deposited in international banks or reinvested in US dollar assets, a process known as the petrodollar cycle. By 1975, all OPEC countries had adopted US dollar pricing, embedding the US dollar in the core of global trade and finance. This supported persistent U.S. budget and trade deficits while suppressing interest rates, strengthening the dollar’s hegemony and granting the U.S. new ‘exorbitant privileges.’ In the 1970s, money market funds emerged as corporate cash management tools, with the first (the Reserve Fund) launching in 1971 with $1 million in assets.

Deregulation, Globalization, and the Eurodollar (1980s-1999)

During the 1980s and 1990s, the dollar's hegemony was consolidated against a backdrop of financial deregulation, the triumph of inflation, and accelerated globalization. Under the leadership of Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker, inflation fell from approximately 13% in 1980 to around 3% in 1983, restoring confidence in the dollar as a stable store of value. By the mid-1980s, the dollar had soared to historic highs, prompting the 1985 Plaza Accord, in which the United States and major allies coordinated a devaluation of the dollar. By 1987, the dollar had fallen by approximately 40% against the yen and the mark, helping to reduce trade imbalances. Financial deregulation, including the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980, eliminated deposit interest rate ceilings and expanded the scope of Federal Reserve services, enabling banks to compete more effectively for deposits. In the 1990s, globalization intensified, and the dollar became the currency of choice in the expanding global capital markets. The eurodollar market flourished, and by the late 1990s, approximately 64% of global debt was denominated in dollars, and the dollar accounted for 59% of foreign exchange reserves and 58% of international payments, solidifying its central position in the global financial system.

Global Financial Crisis and Quantitative Easing (2000s)

The 2000s tested the U.S. banking system and the dollar, particularly during the 2007-2009 global financial crisis, the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression. Although the crisis originated in the U.S. housing and banking sectors, it reinforced the dollar's global safe-haven status. Hedge funds and mortgage lenders began to fail in 2007; by March 2008, Bear Stearns was absorbed by JPMorgan Chase with Federal Reserve support. The crisis peaked with the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, freezing interbank lending and triggering a run on money market funds, with one fund going "below the dollar." Global contagion ensued, as many foreign banks held U.S. mortgage securities or relied on dollar funding. The U.S. responded with a massive response: the Federal Reserve cut interest rates to near zero, created emergency lending facilities, and opened dollar swap lines with foreign central banks, becoming the world's lender of last resort. The Treasury launched the $700 billion TARP program to recapitalize banks and stabilize institutions like AIG. The FDIC guaranteed bank debt and expanded deposit insurance to $250,000. Starting in late 2008, the Federal Reserve initiated quantitative easing (QE), purchasing long-term Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities. The 2010 Dodd-Frank Act imposed stricter capital and liquidity rules, while subsequent rounds of QE (QE2 in 2010 and QE3 from 2012 to 2014) supported a slow but steady recovery, expanding the Fed's balance sheet to $4.5 trillion.

Pandemic Quantitative Easing and De-Dollarization (2010-2025)

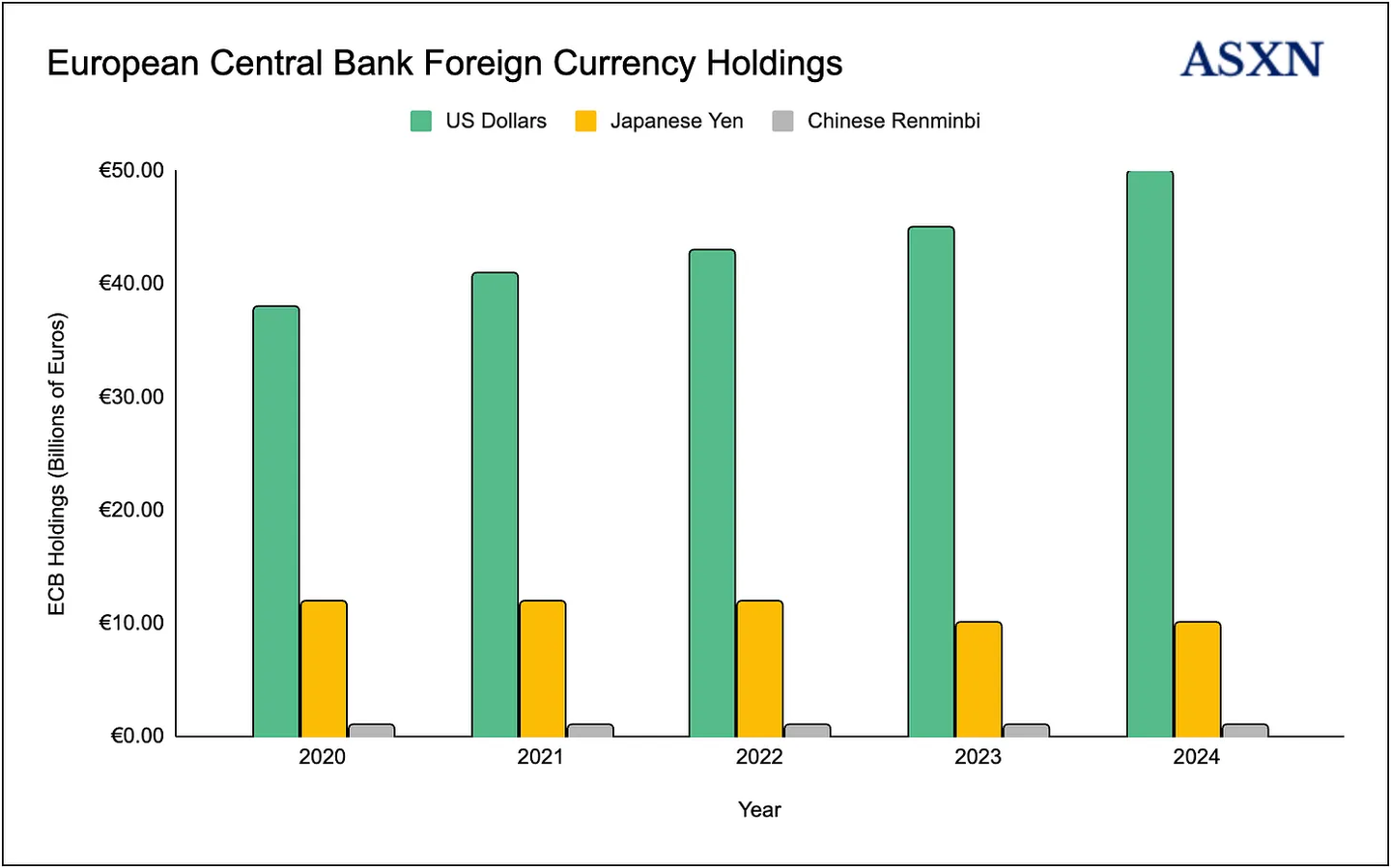

Over the past decade, the United States has experienced an unprecedented expansion of monetary stimulus. After the conclusion of QE3 in 2014, the Federal Reserve's balance sheet exceeded $4 trillion, four times its pre-crisis level. A brief attempt to reduce its balance sheet in 2017 was interrupted when the 2019 repo market shock exposed the system's dependence on Fed liquidity. In response to COVID-19, the Fed cut interest rates to zero, restarted QE, and introduced emergency facilities, nearly doubling its assets to nearly $9 trillion by mid-2022, representing 36% of GDP. Meanwhile, fiscal stimulus exceeding $5 trillion pushed federal debt to 98% of GDP in fiscal 2024. Inflation reached 9% in 2022, forcing the Fed to reverse its policy, raising interest rates above 5% and shrinking its balance sheet to $6.8 trillion by early 2025. The US dollar still dominates foreign exchange markets, accounting for 88% of transactions reported by the BIS, but its share of global reserves has fallen from 66% in 2015 to 57.8% by the fourth quarter of 2024. The trend toward de-dollarization is accelerating: Russia’s frozen reserves due to the Ukraine invasion have sparked concerns about dollar risks; Saudi Arabia’s failure to renew the petrodollar agreement marked a symbolic shift; Iran is increasingly settling trade in non-dollar currencies; and China is promoting the use of RMB for trade settlement, especially after Trump’s tariff war exacerbated Sino-US tensions.

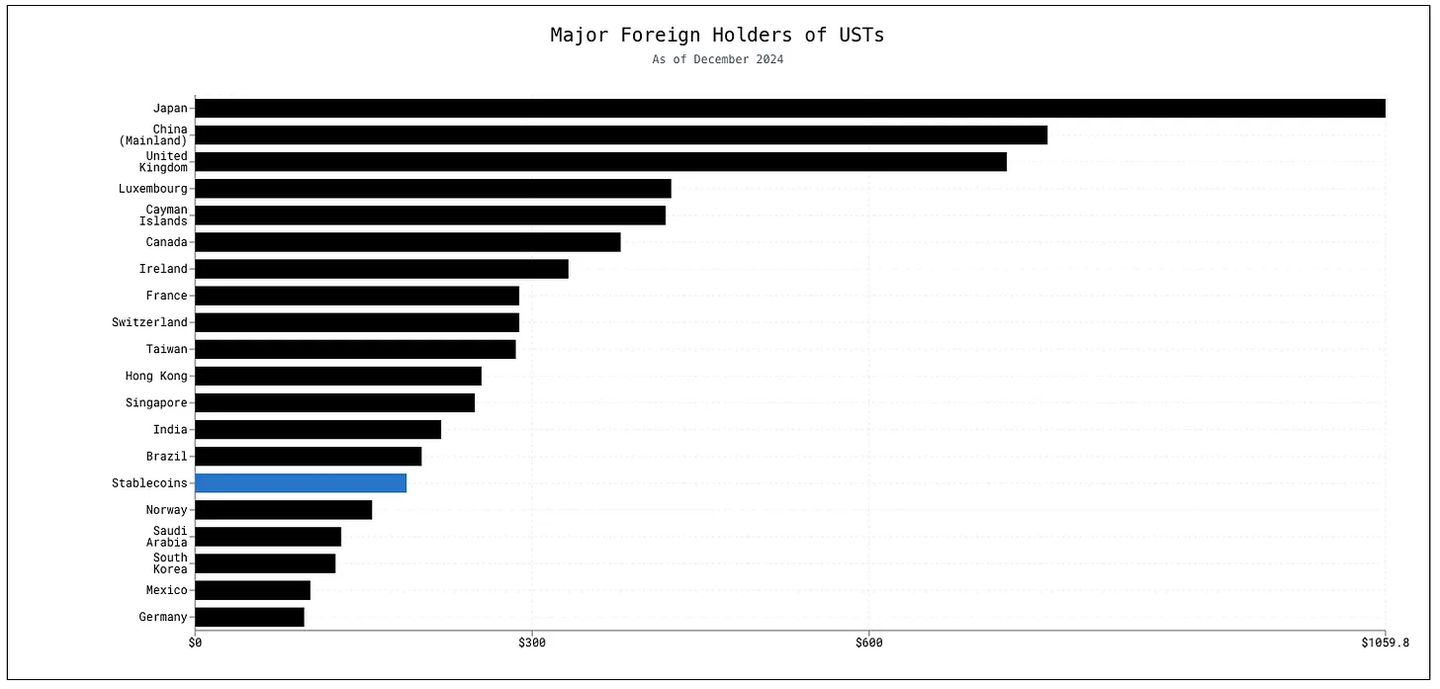

Since Nixon closed the gold window in 1971, the US dollar has floated freely as a pure fiat currency. Today, the 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks issue the single national currency—Federal Reserve Notes—while the US Treasury mints coins. Almost all other "dollars" exist in the form of electronic bank deposits settled through the Federal Reserve System. The federal government finances itself by selling Treasury bonds, and the Treasury market remains the world's deepest pool of safe-haven assets: foreigners hold approximately $8.8 trillion in Treasury bonds, with Japan alone holding $1.13 trillion. Sustained global demand has kept yields relatively low, with the 10-year Treasury yield hovering around 4%, even though publicly held debt now stands at 122% of GDP and continues to climb. This "reserve currency dividend" is the flip side of the dollar's hegemony: the United States can run large deficits and borrow cheaply because dollar assets are needed globally for trade, security, and regulation.

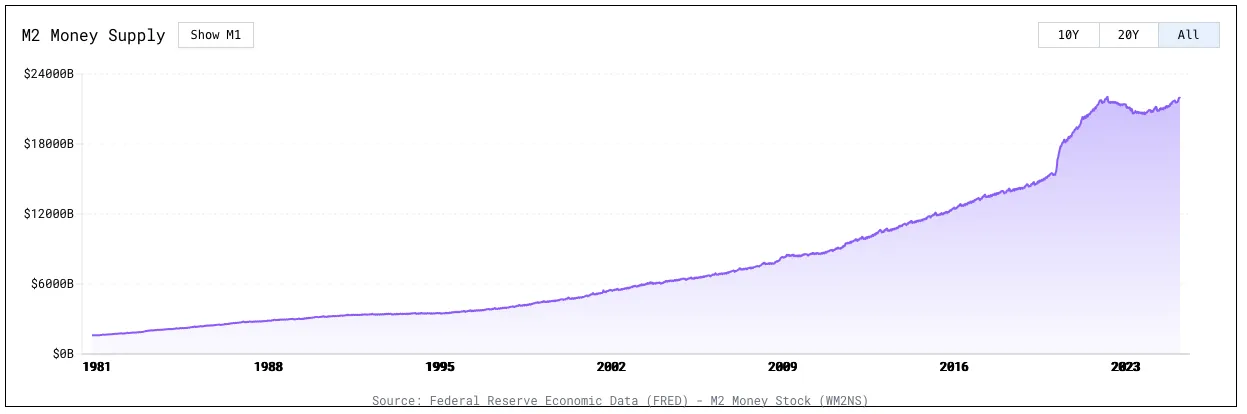

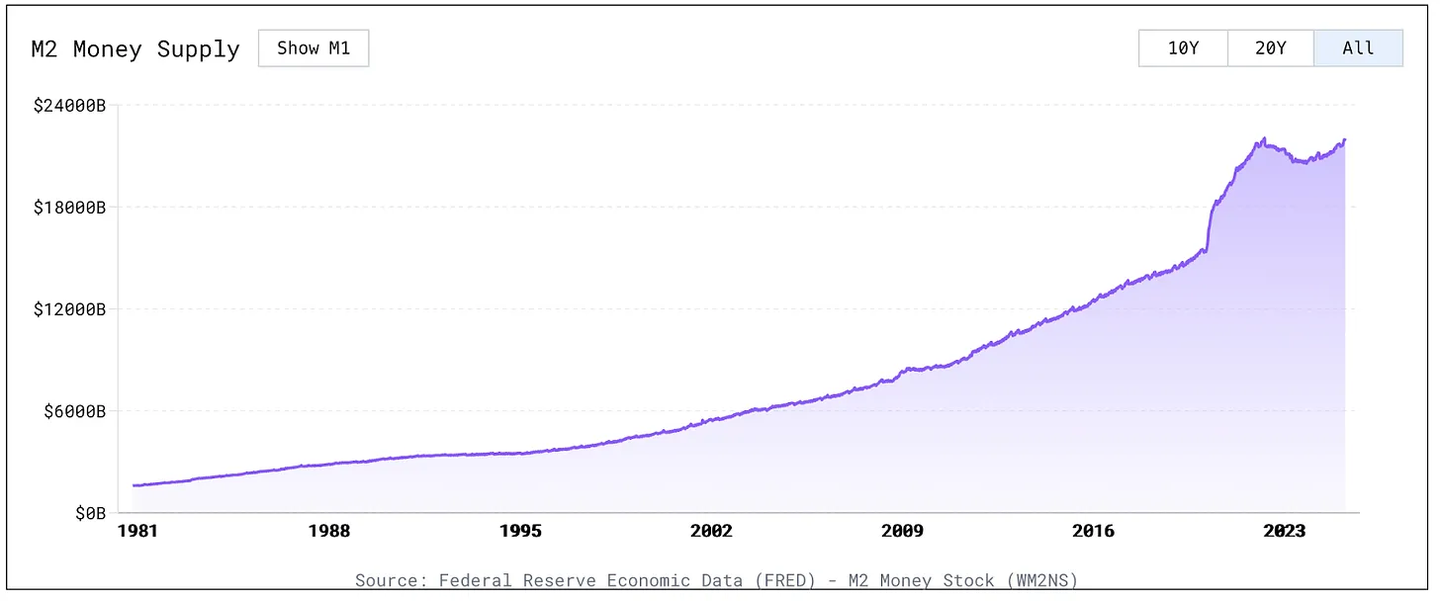

Another hallmark of the modern U.S. monetary system is its high degree of digitization. Of the approximately $21 trillion in broad money (M2), approximately $18.5 trillion (nearly 90%) consists of digital ledger entries in commercial banks or Federal Reserve databases. Physical currency in circulation is only $2.36 trillion, and the Federal Reserve estimates that approximately 60% (particularly $100 bills) is held overseas as a portable store of value. Despite the digitization of currency, most U.S. retail payments still rely on legacy infrastructure such as the half-century-old ACH system, with transfers typically settling the next day or longer.

In short, today’s dollar is primarily digital, officially unified, based on fiat currency, and globally coveted, but its payment networks are only partially modernized, and the size of the federal balance sheet and its future affordability become key long-term concerns for the system.

Stablecoin Overview

Stablecoins represent the next stage in the evolution of money and payments systems, laying the foundation for the financial system with faster settlement, lower fees, seamless cross-border functionality, native programmability, and a robust audit trail. They essentially encapsulate the US dollar in software, enabling it to move at the speed of light anywhere the internet is connected. Simply put, stablecoins are the fastest-acting form of the US dollar.

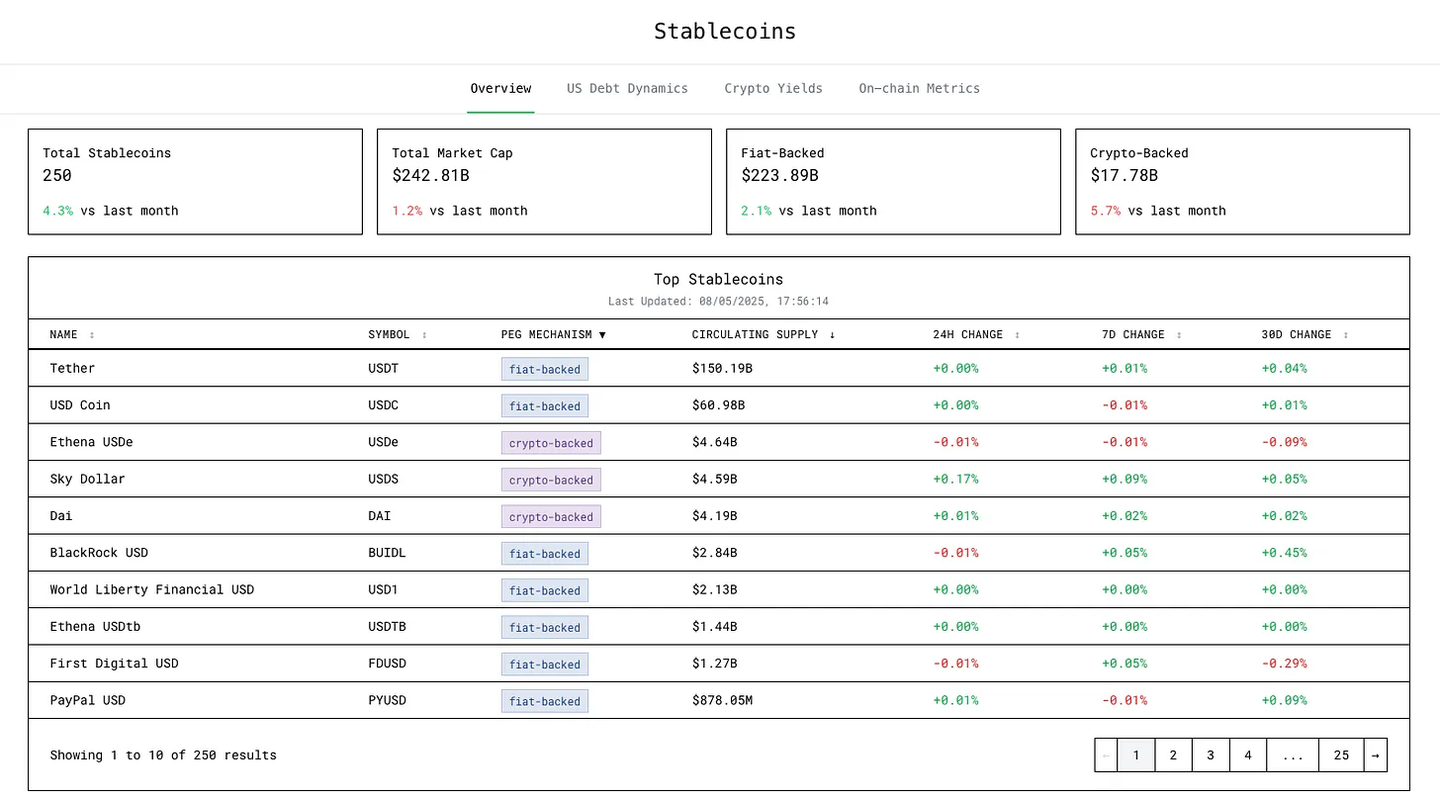

Stablecoins have become the most compelling product-market fit in cryptocurrency, with their growth trajectory reflecting extraordinary adoption. The market has expanded from a total market capitalization of $30 million in 2018 to over $250 billion today, achieving a compound annual growth rate of 263%. Initially used as a crypto-native collateral and settlement mechanism, particularly by market makers and arbitrageurs, stablecoins have evolved into a widely adopted financial primitive. Trading firms and market makers now routinely hold stablecoins on their balance sheets, while decentralized finance (DeFi) protocols have deeply embedded stablecoins into collateral structures and trading pairs. Centralized exchanges are increasingly shifting from Bitcoin-collateralized perpetual contracts to stablecoin-based margin trading. Beyond crypto's internal applications, stablecoins are also gaining traction as a store of value and a fast, low-cost remittance tool among citizens in regions of high inflation or political instability. This broader adoption is driven by significant improvements in infrastructure, including more efficient on- and off-ramps, high-throughput, low-fee blockchains, better-designed wallets, and user-friendly applications driven by advances in private key management.

Stablecoin categories

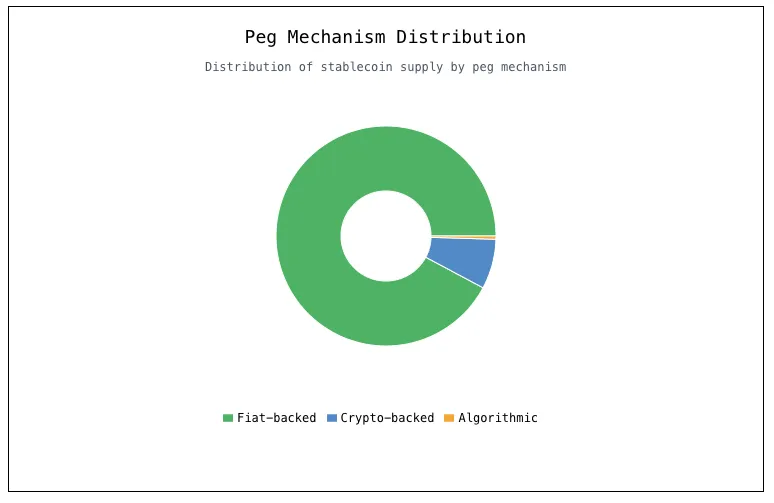

Today's stablecoin ecosystem encompasses several different types of stablecoins, primarily distinguished by their collateral backing, degree of decentralization, and the mechanisms used to maintain their price peg. Fiat-backed stablecoins dominate the market, accounting for over 92% of the total stablecoin market capitalization. Other categories include cryptocurrency-backed stablecoins, algorithmic stablecoins, and, more recently, strategy-backed stablecoins. Broadly speaking, a stablecoin is a digital token that maintains a 1:1 value with a defined currency (usually the US dollar).

Fiat-backed stablecoins

Fiat-backed stablecoins are similar to bearer banknotes from the U.S. national banking era (1865-1913): Back then, banks issued notes redeemable for government greenbacks or gold and silver, their value dependent on the bank's creditworthiness and the holder's ability to redeem them. Today's fiat-backed stablecoins promise 1:1 convertibility with a given fiat currency, but just as 19th-century bearers relied on secondary markets to redeem notes they couldn't directly redeem, modern users rely on platforms like Uniswap or centralized exchanges to redeem tokens for dollars at par (if direct redemption isn't possible). This reliable convertibility—enforced by audited reserves and a robust trading infrastructure—instills the same confidence in fiat-backed stablecoins as the broad convertibility guarantee of banknotes over a century ago.

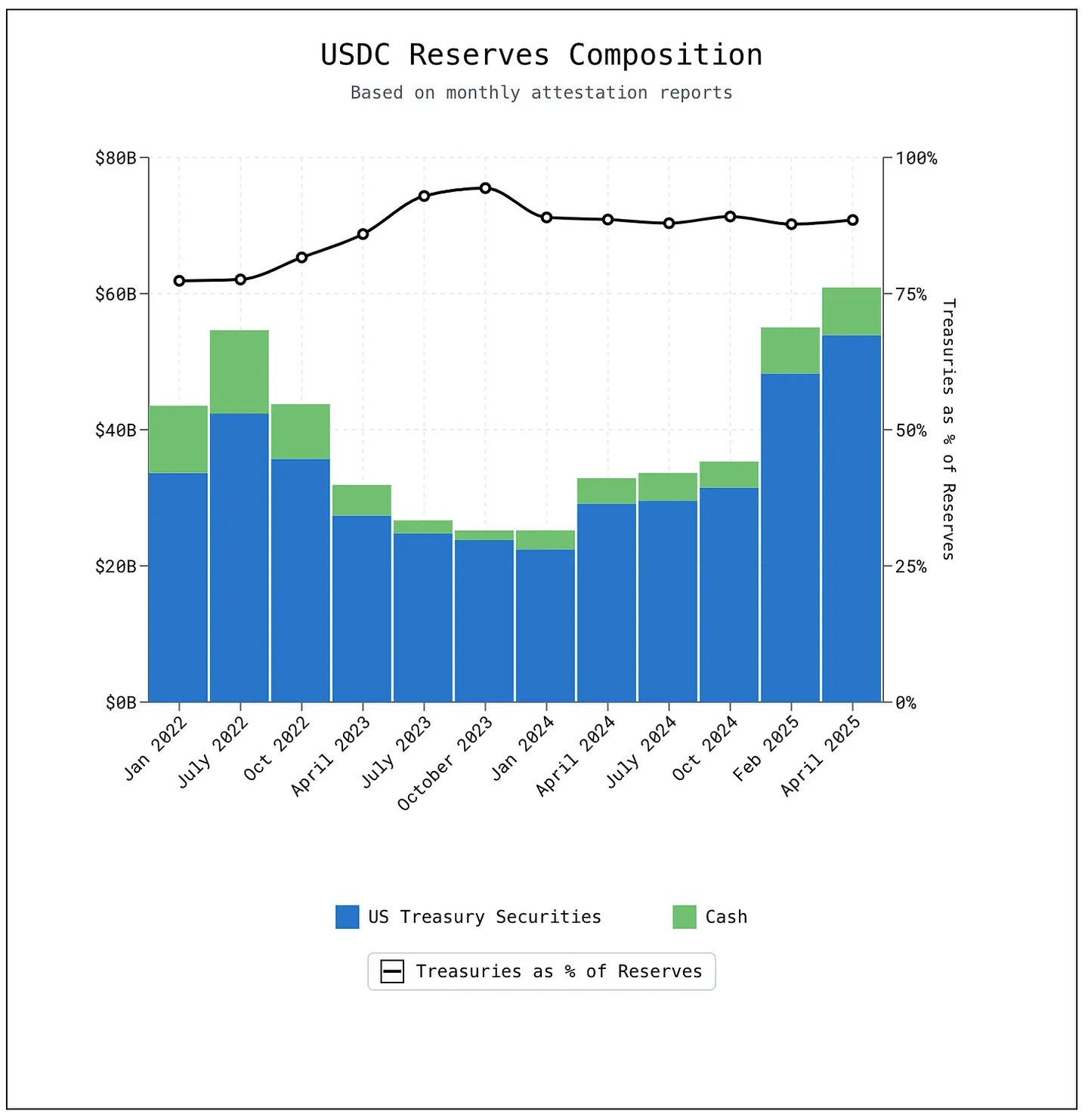

Fiat-backed stablecoins maintain a 1:1 peg by fully collateralizing each digital token with an equivalent amount of fiat currency held off-chain. For example, each USDC token is backed by a combination of $1 in cash and short-term U.S. government debt. Based on current reserve disclosures, each USDC is backed by approximately $0.885 in U.S. Treasuries and $0.115 in cash. The cash portion is held by regulated financial institutions, while the Treasury bonds (including short-term securities and overnight Treasury repurchase agreements) are held in custody by Bank of New York Mellon and managed by BlackRock.

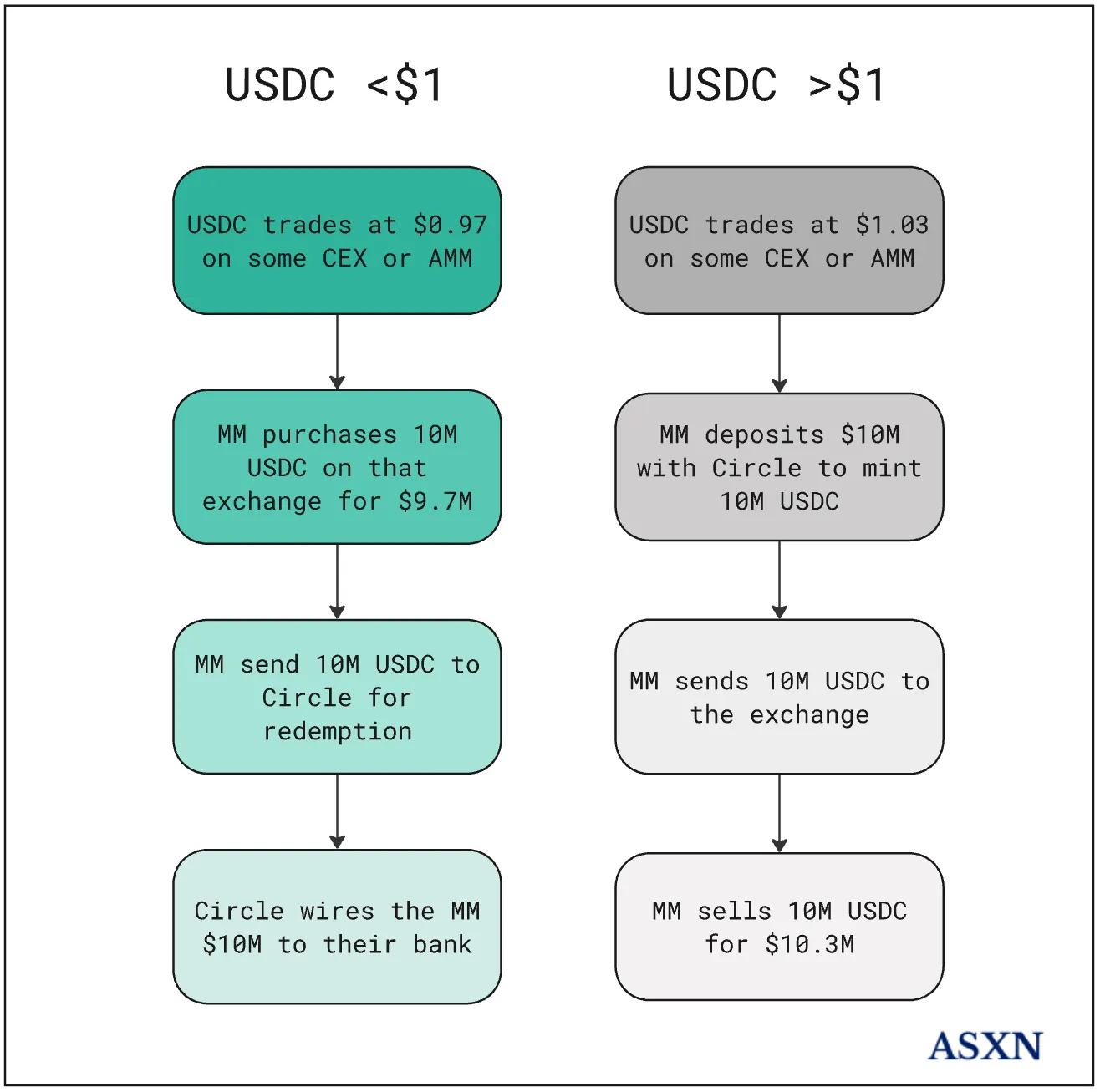

Typically, only certain entities can mint and redeem fiat-backed stablecoins. For example, Circle Mint clients (businesses and institutions with verified accounts) can redeem USDC directly through Circle at a 1:1 ratio. Redemptions are initiated by sending USDC to the smart contract's destroy function and submitting a redemption request via the Circle Mint dashboard or API. Clients can choose between two options: Standard Redemption, which offers near-real-time settlement and no fees for up to $15 million per day (a 0.1% fee applies to any amount above); or Basic Redemption, which is completely fee-free but with a settlement time of up to two business days. Once processed, Circle transfers the USD to the client's linked bank account via ACH or wire transfer, depending on the selected payment channel. This structure supports USDC's 1:1 peg through arbitrage: when secondary markets deviate from parity, traders can capitalize on the difference, helping to restore price stability.

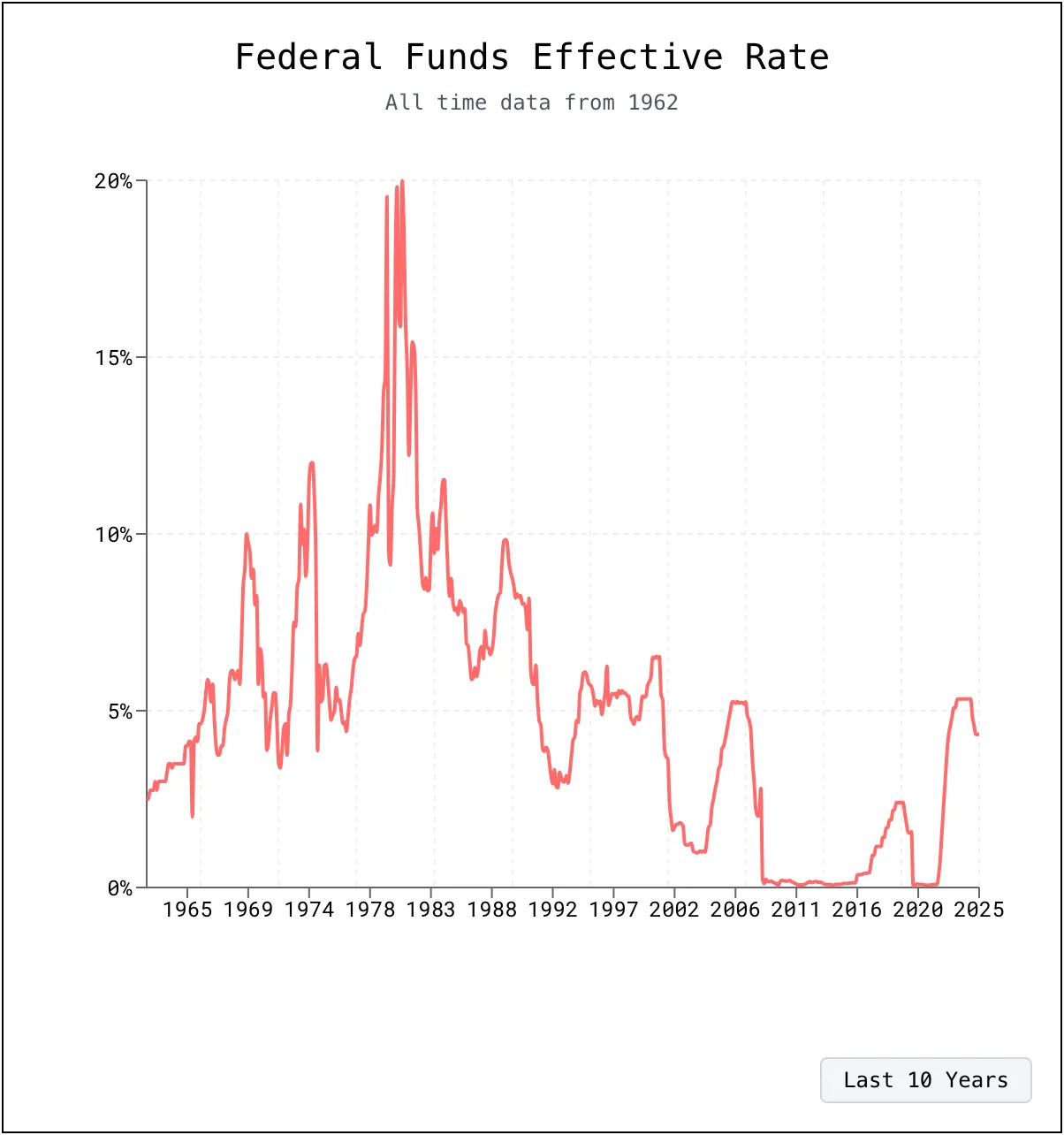

Stablecoin issuers primarily earn income by investing their reserves in interest-bearing U.S. debt instruments. For example, Tether earned approximately $7 billion from its holdings of U.S. Treasuries and repurchase agreements in 2024. Therefore, stablecoin issuers have an incentive to expand their supply, enabling them to invest more capital and capture returns close to the federal funds rate (currently around 4.25%).

Fiat-backed stablecoins bear strong similarities to money market funds (MMFs). Following the Great Depression, the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 was enacted to prevent commercial banks from engaging in risky practices that led to their failure. One provision, Regulation Q, capped the interest rates banks could offer on deposits. Because market interest rates exceeded the deposit rate cap, depositors missed out on yield opportunities. Bruce Bent and Henry Brown launched the first money market mutual fund in 1971, pooling cash from small investors to purchase short-term commercial paper and repurchase agreements. Unconstrained by Regulation Q's interest rate caps (because they were managed by investment companies), these funds could offer returns unmatched by banks while maintaining a $1 per share value.

The similarities between fiat-backed stablecoins and MMFs extend beyond their structural design. Their regulatory and political debates are also highly similar. When MMFs first emerged, they faced the same criticisms as stablecoins today, including concerns about financial stability, insufficient regulation, and systemic risk:

- Financial stability risks: Money market funds (MMFs) do not have federal deposit insurance or central bank backing, unlike regulated banks. This structural flaw makes them vulnerable to liquidity crises and investor runs, as demonstrated during the 2008 financial crisis.

- Regulatory arbitrage: MMFs effectively mimic core banking functions, such as providing a stable dollar-denominated store of value, but are not subject to the strict regulatory and capital frameworks of traditional depository institutions. This creates a parallel credit system with less regulation.

- Monetary Policy Erosion: The growth of MMFs could undermine the effectiveness of the Federal Reserve's policy tools. As assets move from the regulated banking system to less regulated instruments, the effectiveness of tools such as reserve requirements declines, weakening the central bank's ability to control liquidity and credit conditions.

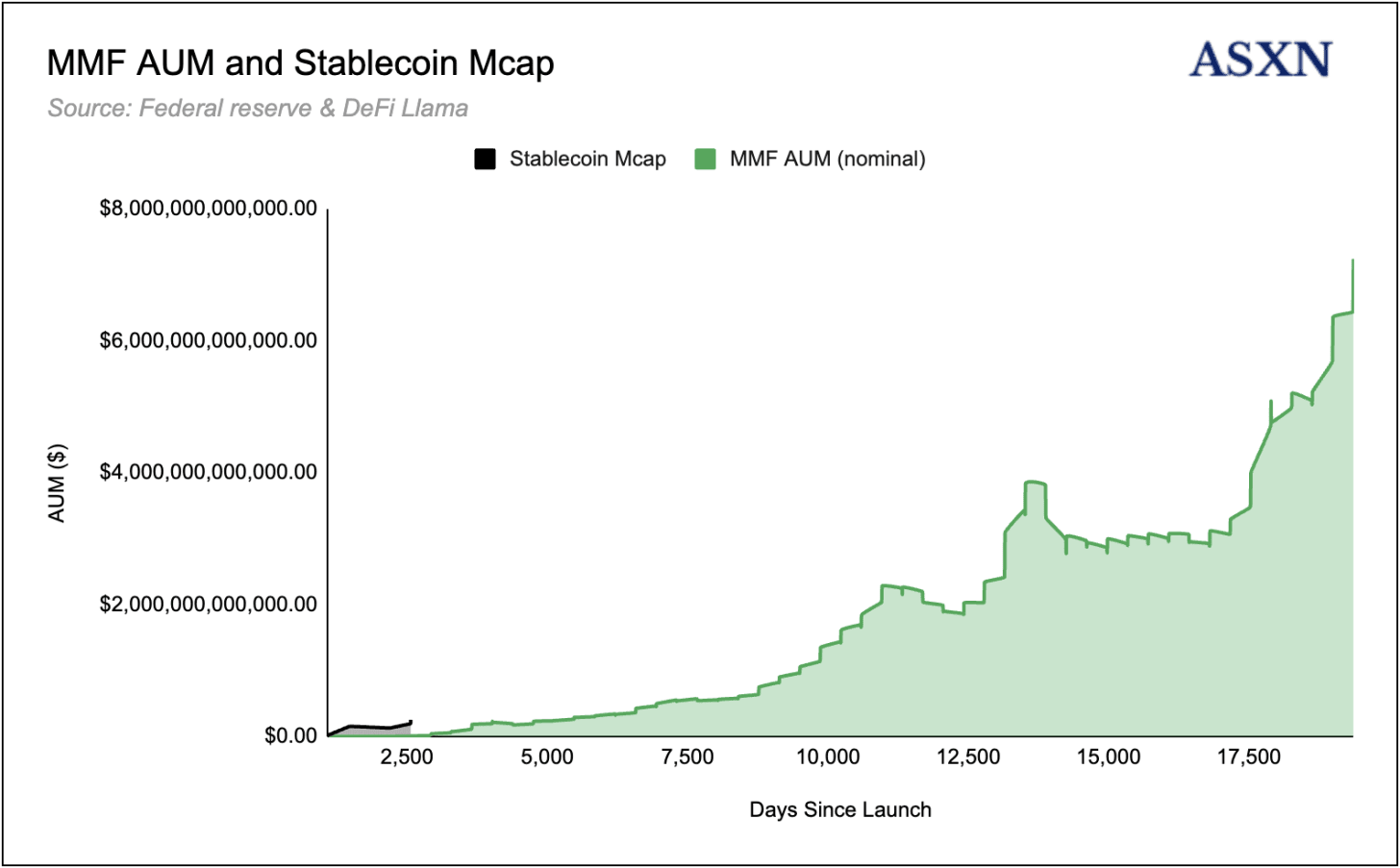

Although introduced in the early 1970s, MMFs did not begin to attract significant assets under management (AUM) until financial deregulation, legislative support, and technological advances (such as electronic settlement systems and the internet) laid the foundation. A key moment came with the passage of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act in November 1999, which repealed key provisions of the Banking Act of 1933 and removed long-standing legal barriers to the sponsorship and distribution of investment funds by commercial banks. This regulatory shift enabled banks to fully integrate MMFs into their product portfolios, becoming part of the "financial supermarket" model. Banks quickly exploited these new powers, launching and distributing their own MMFs as part of core deposit accounts and Treasury-like yield products, attracting record amounts of capital from both institutional and retail investors. By the end of 1998, before the passage of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, the US MMF industry had reached approximately $1.4 trillion in assets. Despite the turmoil caused by the 2008 financial crisis, MMFs continued to grow, reaching approximately $3.8 trillion in AUM by the end of 2008. In many ways, its growth pattern mirrors the current trajectory of stablecoins, which similarly benefit from structural tailwinds and the evolution of financial infrastructure.

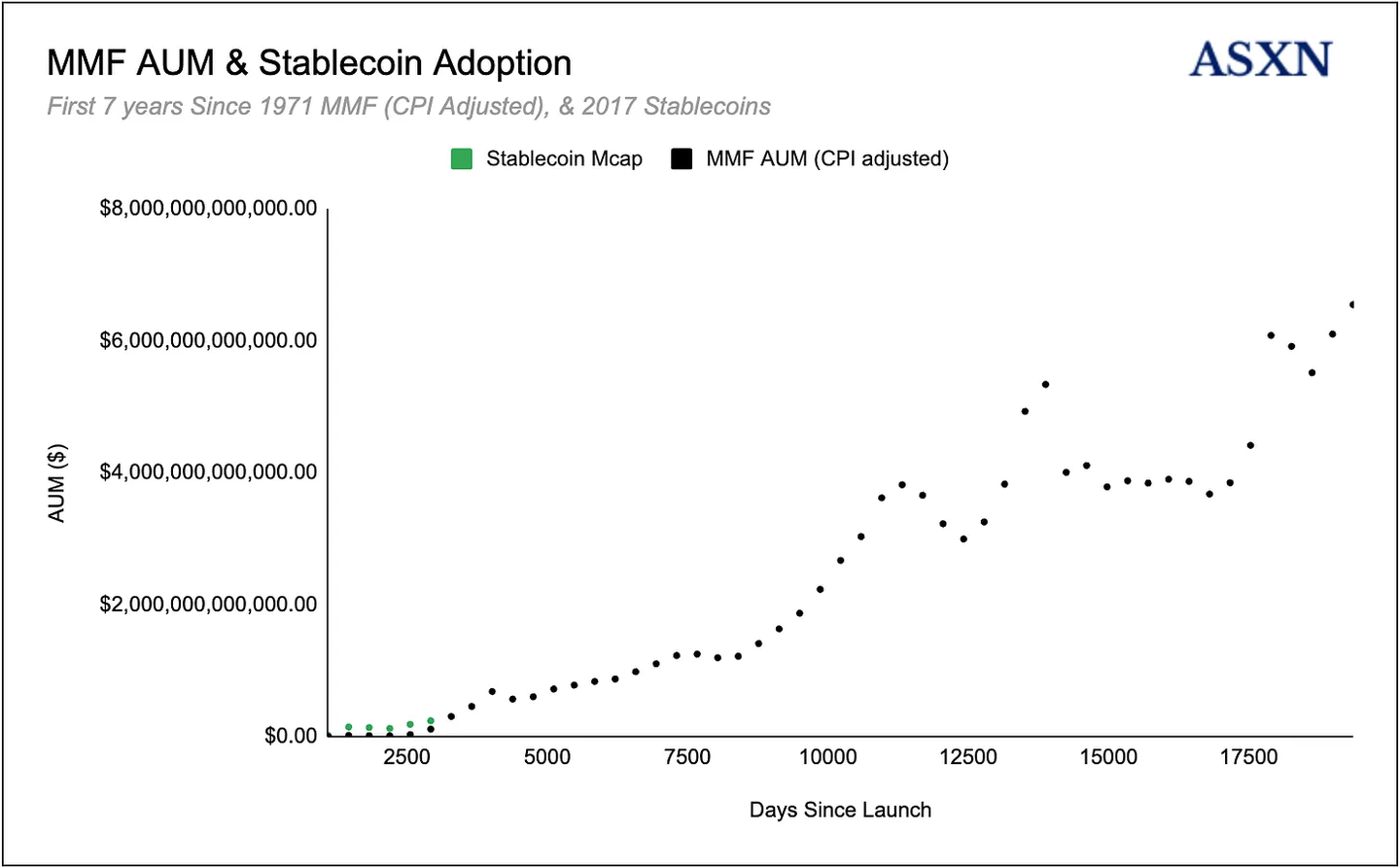

Assets under management (AUM) within MMFs now exceed $7 trillion and continue to grow steadily. By comparison, seven years after their launch, AUM was just $12.8 billion, or approximately $62.8 billion in today's dollars. By this measure, stablecoins were nearly four times ahead of MMFs at a similar stage in their lifecycle. Examining the trajectory of MMFs' inflation-adjusted AUM reveals a strikingly similar growth path for stablecoins. Over the next 15,000 days (approximately 41 years), MMFs' real AUM grew 55-fold, driven by broader distribution, regulatory clarity, and technological advances in financial infrastructure.

Cryptocurrency-backed stablecoins

Crypto-backed stablecoins are very similar to private banknotes from the United States' free banking era (1837-1862), a period that predated the National Bank Act of 1863-64 and the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. In the absence of federal regulation, states enacted "free banking" laws, allowing groups that met minimum capital and collateral requirements (usually state bonds) to open banks. By 1860, over 8,000 different banknotes were in circulation, each trading at a discount or premium depending on the issuer's creditworthiness, the cost of redemption for gold and silver, and local market conditions. Similar to today's cryptocurrency-backed stablecoin issuers, these free banks accepted gold and silver coins and (in some states) short-term government securities as reserves, then issued their own notes against those reserves while making loans under a fractional reserve system.

This money creation mechanism still exists today and it works like this:

- A customer deposits $1,000 in a checking account, creating a $1,000 asset (reserves) and a $1,000 liability (deposits) on the bank's balance sheet.

- Regulators require (for example) a 10% reserve ratio, so that for $1,000 in deposits, the bank holds $100 in reserves and can lend $900.

- Each time a loan is made and redeposited at another bank, the process repeats, multiplying the original monetary base to create a larger total amount of bank deposits. In fact, most broad money (M2) is created in this way.

Cryptocurrency-backed stablecoins operate in a similar manner, but most utilize an over-collateralized lending system due to its decentralized and KYC-free nature. Typically, users deposit collateral (e.g., $1,000 worth of BTC) into the protocol, which then mints up to $800 worth of stablecoins, reflecting an 80% loan-to-value (LTV) ratio. To prevent collateral devaluation from leading to system insolvency, the protocol enforces liquidation thresholds. If the collateral value falls below a specified LTV ratio, the system automatically liquidates the user's BTC to cover the outstanding debt, thus preventing the accumulation of bad debt.

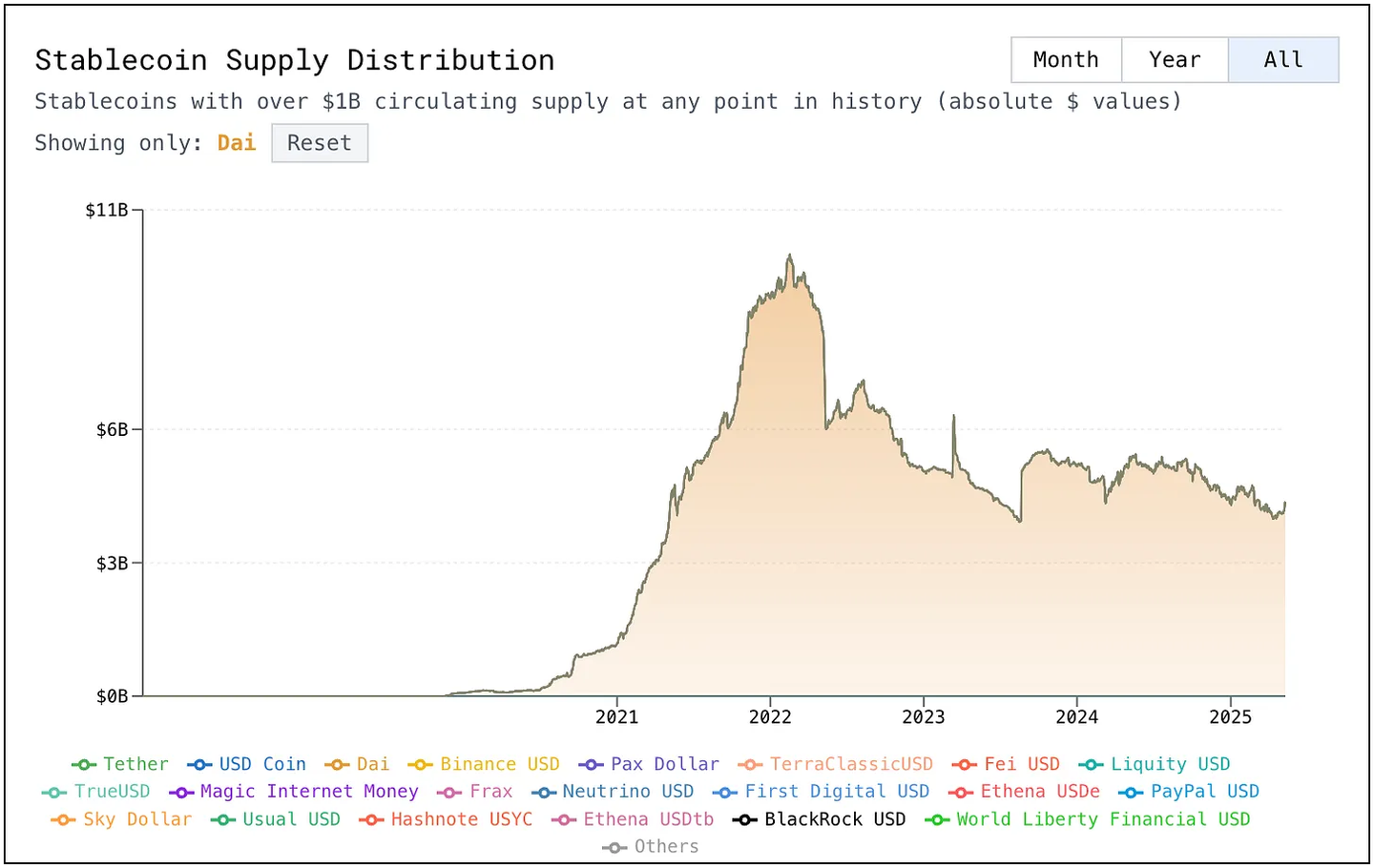

The Maker/Sky protocol issues the largest decentralized cryptocurrency-backed stablecoins in the space (DAI and USDS), and has done so since the launch of single-collateral DAI in 2017. Users mint DAI by depositing accepted collateral (cryptoassets such as ETH, wBTC, stETH, rETH, USDC, Gemini Dollar, and tokenized real-world assets including US Treasuries, real estate-backed tokens, and loans) into Vaults (formerly CDPs). Each collateral type is required to meet a minimum collateralization ratio (e.g., 150% for ETH). If the Vault value falls below this threshold, it will be liquidated to maintain the solvency of the system. The process is as follows:

- A user deposits 1 wBTC worth $100,000 into a Maker Vault as collateral. The wBTC Vault type requires a 150% collateralization ratio (66.67% LTV).

- Users can mint up to 66,666 DAI ($100,000 * 66.67%).

- If a user mints 50,000 DAI, leaving a buffer above the minimum ratio, the Vault will hold 1 wBTC as collateral for the 50,000 DAI debt, giving a collateralization ratio of 200% or 50% LTV.

- If the value of wBTC drops below $75,000, the Vault’s collateralization ratio will fall below 150%, and the Vault will become undercollateralized.

- At this point, the Vault will face liquidation: some wBTC will be auctioned/sold to cover the DAI debt, plus a liquidation penalty.

- If a user wishes to unlock the collateral at any time, they must repay 50,000 DAI (plus the accumulated stability fee) and can then withdraw wBTC.

This is very similar to how banks create new money by lending, but using liquid on-chain collateral. Each stablecoin is similar to a different banknote in the era of free banking. Holders need to assess the risk of stablecoins based on the following non-exhaustive factors:

- The quality, liquidity, and volatility of the collateral backing on-chain loans.

- The ability for the protocol to safely unwind undercollateralized loans.

- Security of smart contracts and mechanism design.

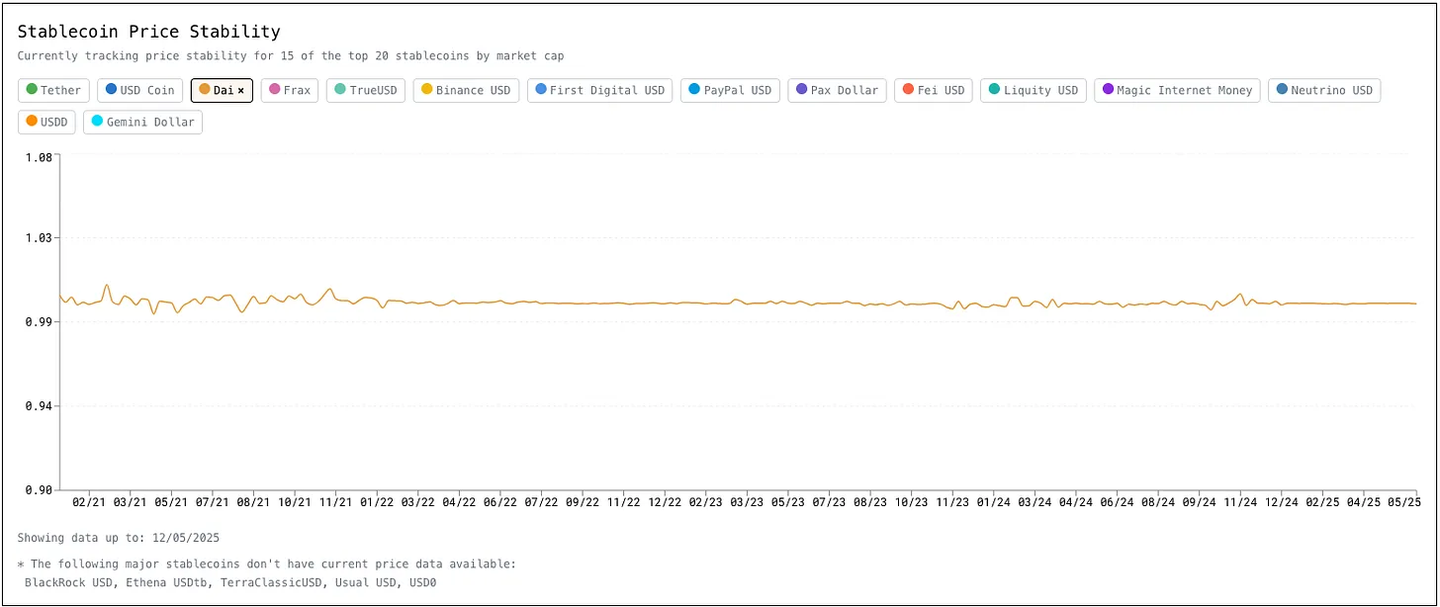

For example, during the March 2020 market crash, ETH plummeted 53% in two days, exposing significant weaknesses in DAI's sole ETH collateralization model. The sharp price drop triggered massive liquidations, leading to congestion on the Ethereum network and delayed oracle price feeds. Consequently, DAI lost its peg, trading between $0.96 and $1.13 on March 13. This instability highlighted the risks of relying solely on ETH as collateral, prompting the DAI community to propose adding USDC on March 16, 2020, to diversify the risk and improve the peg's stability. Since 2021, DAI has remained relatively stable.

Algorithmic stablecoins

Unlike fiat-backed and cryptocurrency-backed stablecoins, algorithmic stablecoins are not always backed by hard assets, but rather utilize a combination of algorithms and smart contracts to maintain their pegs. We can further categorize algorithmic stablecoins into several models based on Kraken’s analysis:

Seigniorage or Dual-Token Algorithmic Stablecoin

Seigniorage or dual-token algorithmic stablecoins use a dual-token system to maintain stable value. The first token is the stablecoin itself; the second is a bond or utility token, with supply and demand dynamics managed through incentive mechanisms and smart contracts.

When a stablecoin trades above $1, it indicates excess demand. The protocol mints new stablecoins and distributes them, typically to governance or bond token holders. This increase in supply is intended to exert downward pressure on the price, guiding it back toward its $1 target.

Conversely, if the stablecoin price falls below $1, the protocol shrinks the supply by allowing users to purchase bond tokens at a discount (e.g., $0.75). These bonds are redeemable for $1 after the peg is restored. This mechanism incentivizes buyers and reduces the amount of stablecoins in circulation, theoretically helping the price return to parity.

The Terra Luna and UST stablecoins follow this model, with LUNA tokens being burned/minted during price fluctuations to restore UST's value to $1. However, in early 2022, UST lost its $1 peg, and the protocol collapsed due to a loss of trust in the system and a highly inflated LUNA supply. Within days, UST's market capitalization evaporated by approximately $18 billion, and its price plummeted to below 10 cents.

The other two categories of algorithmic stablecoins include:

Rebalancing stablecoins: Rebalancing stablecoins maintain their peg to $1 by directly adjusting the supply in user wallets. When the price is above $1, the token balance increases proportionally; when the price is below $1, the balance decreases. This elastic supply model does not rely on a minting or redemption mechanism. Ampleforth (AMPL) is the most well-known example.

Partially algorithmic stablecoins: These stablecoins combine partial collateral backing with algorithmic supply control. Some of the backing is provided by assets like USDC or ETH, while the remainder relies on programmatic adjustments. Early implementations of FRAX employed this model, maintaining a collateralization ratio below 100%, for example, 90% backed by USDC.

Since the collapse of Terra Luna and UST, experimentation with algorithmic stablecoins has declined sharply, with many projects (such as Frax Finance and Near Protocol) abandoning the model. This retreat stems in part from regulatory resistance: a proposed US bill proposes a two-year ban on new algorithmic stablecoins, while the EU's Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCAR) Act has already implemented a blanket ban on such stablecoins, specifically targeting "intrinsically collateralized" stablecoins. While the appeal of decentralization and capital efficiency may drive some continued experimentation, we expect algorithmic models to remain niche. Depegging risks and an increasingly stringent regulatory environment may limit their role in future stablecoin market growth.

Strategy supports stablecoins

A new category of "stablecoins" has recently emerged—tokens that maintain a $1 denominated value while embedding a yield-generating investment strategy. These instruments are more like shares of USD-denominated, open-ended hedge funds than traditional stablecoins. The concept was first proposed in March 2023 by Arthur Hayes, founder of BitMEX and a pioneer of perpetual futures contracts. In his paper "Introducing NakaDollar," he proposed a hypothetical stablecoin, NUSD, structured as follows: 1 NUSD = 1 USD worth of Bitcoin + a short on a 1 BTC/USD inverse perpetual swap. Inspired by this, Guy Young founded Ethena, whose strategy-backed stablecoin, USDe, has become a leading project in this emerging category.

Each USDe is minted by depositing a crypto asset (such as ETH, BTC, or a liquid collateral token) equivalent to USD, while simultaneously short an equivalent notional value through perpetual swaps or futures. This creates a "long + short" neutral basis trade, where price fluctuations in the underlying asset are offset by the short position, keeping the net portfolio value near $1. This structure allows USDe to remain fully collateralized 1:1 without the over-collateralization buffer typical of traditional cryptocurrency-backed stablecoins.

USDe also has yield-generating properties. Short positions earn funding payments when the perpetual swap funding rate is positive. In this sense, Ethena effectively provides/funds leverage to the market, as demand for leverage in the crypto market is often cyclical but high. Users capture this yield by staking USDe to obtain sUSDe (yield-generating tokens). sUSDe acts as a savings tool, accumulating income from funding rates, liquid staking rewards, and other protocol revenue, while the underlying USDe remains an interest-free stablecoin if left idle. In 2024, sUSDe's average annualized yield was approximately 19%, reflecting the strong demand for leverage and staking rewards in the crypto market.

The launch of Ethena and USDe has inspired many other strategies to support stablecoins, such as Resolv USD and more recently Neutrl, which tokenizes OTC arbitrage trading (long discounted OTC rounds, short perpetuals) through NUSD.

We refer to these strategy-backed stablecoins as USD products or synthetic USD products, but it is important to note that their risk profile differs from what many consider to be traditional stablecoins (i.e., stablecoins backed by Treasury bonds or short-term government debt instruments).

Okay, I'll continue translating your document, starting with the "The Case for Stablecoins" section. I'll maintain the same style as the previous translation, ensuring accurate representation of the original content while maintaining a fluent, professional language. If you have specific requests (such as translating to a specific section, providing a summary, or adjusting the translation depth), please let me know. Below is the translation of the "The Case for Stablecoins" section, and I'll continue translating the subsequent sections in order.

Stablecoin use cases

Store of Value

While most investors, especially Bitcoin investors, recognize that the US dollar is slowly losing purchasing power due to persistent inflation and currency devaluation, as Ray Dalio aptly put it, "the dollar remains the least dirty shirt in the laundry basket." Indeed, over 20% of the global population lives in regimes experiencing inflation rates of 6.5% or higher, and over 51% face inflation worse than that of the United States (2025 data). In countries experiencing hyperinflation, currency devaluation, or strict capital controls, citizens and businesses are increasingly turning to dollar-pegged stablecoins as a store of value. In economies like Argentina, Turkey, Lebanon, Venezuela, and Nigeria, people are choosing to hold digital dollars (such as USDT, USDC, or DAI) rather than rapidly depreciating local currencies. In these environments, stablecoins serve more as digital savings accounts than as payment channels, providing a more stable way to protect purchasing power.

The effectiveness of a currency as a store of value depends on several core economic fundamentals. When these fundamentals deteriorate, confidence in the currency will gradually weaken. Key drivers include:

Inflation: Low and stable inflation is essential for a currency to maintain its value. High inflation can quickly erode purchasing power.

Monetary policy: If markets perceive a central bank as lacking discipline or independence—for example, by printing money to finance deficits or pursuing unorthodox policies—the currency’s value could plummet. Turkey is a case in point: despite average inflation exceeding 40%, the central bank cut interest rates in 2022-2023, undermining its credibility and contributing to a 300% decline in the lira’s value between 2020 and 2023.

Fiscal discipline: Unsustainable fiscal policies can lead to currency devaluation. If a government runs chronic deficits and accumulates debt that investors doubt it can repay, it may resort to debt monetization (i.e., printing money). This expands the money supply, triggers inflation, and undermines the value of the currency. For example, Lebanon's government debt default and deficit monetization in the late 2010s led to a currency collapse and triple-digit inflation.

Money supply: The rate of money supply expansion relative to actual economic growth affects long-term value. If money supply growth far outstrips economic growth (as is often the case when central banks finance government spending or bailout banks), it typically leads to inflation and devaluation. For example, Venezuela's money supply surged during hyperinflation, leading to the collapse of the bolivar as a store of value.

Capital Controls and Convertibility: A currency's appeal as a store of value also depends on the ability to freely convert, or transfer, its value. When governments impose capital controls—restricting access to foreign exchange, cross-border transfers, or fixing unrealistic exchange rates—currencies become "trapped," often overvalued domestically. This erodes confidence, as people worry about not being able to exit to stable assets when needed.

Political and Institutional Stability: Broader political risk factors also play a role. Regime instability, threats of expropriation or bank freezes, and a lack of rule of law can all undermine confidence in the local currency and banks. Lebanon's banking crisis is a prime example: in 2019-2020, banks implemented informal capital controls and froze deposits, undermining trust in holding wealth in local institutions.

For many countries and the majority of the global population, the US dollar offers relative advantages along key dimensions: lower inflation, fewer capital controls, and greater political stability. Furthermore, the dollar provides access to the world's most liquid financial markets and is backed by a (mostly) disciplined Federal Reserve System that sets clear targets around core economic indicators.

We can gain insight into how citizens in emerging economies are using stablecoins to protect their wealth through a few case studies:

Argentina

Argentina is a prime example of capital flight to stable value through cryptocurrency. Decades of chronic inflation and repeated currency crises have eroded public trust in the peso. While the current inflation rate is around 20%, Argentina experienced a high of 143% in 2023, pushing approximately 40% of Argentines into poverty. In December 2023, newly elected President Javier Milei devalued the peso by 50%, calling it "shock therapy."

“In response to the economic crisis, some Argentines have turned to the black market to obtain foreign currency, most commonly U.S. dollars. These ‘blue dollars’ are U.S. dollars traded at a parallel, informal exchange rate and are often purchased through clandestine exchange offices called ‘cuevas’ across the country. Others have explored dollar-pegged stablecoins, which is reflected in our data.

We analyzed monthly stablecoin trading volume against the Argentine Peso (ARS) on Bitso, a leading Latin American exchange, and found that a sustained decline in the peso’s value consistently triggered a surge in stablecoin trading. For example, when the value of ARS fell below $0.004 in July 2023, stablecoin trading surged to over $1 million the following month. Similarly, when the value of ARS fell below $0.002 in December 2023 (the time of President Milley’s announcement), stablecoin trading exceeded $10 million the following month. — Chainalysis

USDT is widely used in some circles for daily transactions, effectively becoming a parallel currency. Even Argentine tax authorities have taken notice: the province of Mendoza began accepting stablecoins for tax payments in 2022, legitimizing their de facto role as currency. For ordinary Argentines, stablecoins are a lifeline: a way to hold "dollars" that won't depreciate rapidly, without requiring special permission.

Lebanon

Lebanon's financial collapse, which began in 2019, demonstrates why ordinary citizens turn to stablecoins when traditional financial systems collapse. The Lebanese pound (LBP) lost over 98% of its value during the crisis, destroying personal savings and driving inflation to over 200% by 2023. Meanwhile, banks froze dollar accounts and imposed arbitrary withdrawal restrictions, effectively imposing capital controls and cutting off depositors' access to their funds. Amid this financial paralysis, many Lebanese turned to crypto assets, particularly stablecoins, as a practical alternative to the dollar.

Tether (USDT) has rapidly gained popularity in Lebanon, becoming the de facto quote currency for local money changers and traders, fostering a parallel crypto-based exchange market. One report described USDT as "the cryptocurrency of choice for exchanges circumventing banking restrictions." Its peer-to-peer transferability allows users to bypass the frozen banking system and the official currency peg, trading USDT for pounds or other cryptocurrencies through Telegram groups or local brokers. Holding USDT provides users with a stable store of value protected from hyperinflation and the ability to make online purchases or transfer funds across borders—functions typically blocked by capital controls.

Lebanon has also highlighted the trust advantages of stablecoins, particularly when used with self-custodial wallets. With domestic banks widely viewed as broken and untrustworthy, storing funds in personal crypto wallets provides users with a sense of control and security. Many Lebanese use stablecoins as digital savings accounts, holding USDT or USDC for weeks or months, converting to LBP only when spending.

Summary of Stablecoins as a Store of Value

For the sake of brevity, we've only listed a few case studies, but Chainalysis provides a good overview of similar trends in Latin America. Overall, dollar-pegged stablecoins (such as USDT, USDC, and DAI) have strong appeal in economies with high inflation and capital constraints. The following factors make them an attractive store of value:

Purchasing Power Protection: For someone in Argentina or Nigeria, switching from a currency that loses 20-100% of its value annually to a dollar-pegged stablecoin instantly dollarizes and halts the erosion of purchasing power. Even with US inflation at around 3-4%, the contrast remains significant. Stablecoins inherit the relative stability and trustworthiness of the dollar, making them an attractive alternative in countries where trust in their local currencies is crumbling.

Self-custody: Users hold the cryptographic keys to their own addresses, meaning their assets are immune to local bank solvency or government freeze orders. This is a powerful feature in places like Lebanon and Nigeria where banks could be bailed out or withdrawals arbitrarily restricted. With stablecoins, users can store $100 or $100,000 on secure hardware wallets or even paper backups without the risk of local authorities devaluing or confiscating their funds, unless the global crypto network is compromised.

Liquidity: Stablecoins are not only used for passive savings, they are also highly liquid for transactions. This makes them functional in everyday life. Traditional forms of dollar exposure (such as offshore accounts or physical cash) cannot match this liquidity.

Censorship resistance: Traditional dollar corridors (banks or remittance services) are susceptible to surveillance, censorship, or political interference. Stablecoins, especially when traded on peer-to-peer or decentralized platforms, offer increased privacy and censorship resistance.

For these reasons, stablecoin activity has grown rapidly in Latin American and African countries, with transfers under $1 million increasing by more than 40%, as determined by Chainalysis’ deanonymization software.

money transfer

Remittances are one of the primary use cases for stablecoins. Every year, tens of millions of workers send part of their wages back home, supporting over 200 million beneficiaries worldwide. In 2024, global remittance flows reached approximately $905 billion, equivalent to the GDP of a medium-developed economy. This figure is expected to continue to grow in 2025. Approximately 76% of this total, or approximately $685 billion, flows to low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Remittances in these regions are often the lifeblood of household economies, covering basic needs such as food, education, and healthcare.

Remittances are highly concentrated in LMICs, which often face the same store-of-value challenges we mentioned earlier, including weak local currencies, capital controls, and political instability. This makes cross-border inflows particularly vulnerable to value erosion—creating a strong case for the adoption of stablecoins as a more resilient and efficient alternative.

Stablecoins are well-suited for remittances, not only because they offer a more stable store of value (especially dollar-pegged stablecoins), but also because they enable faster, cheaper, and more secure cross-border transfers. Currently, most remittances are sent through traditional banks, money transfer operators like Western Union and MoneyGram, or mobile money platforms like M-Pesa in certain regions. While these channels are widely used, they often involve high fees and delayed settlements. In the fourth quarter of 2023, the global average cost of sending $200 was approximately 6.4%. In some corridors, this figure exceeded 10%. For those on a tight budget, such a high percentage of remittance losses is a significant burden. These costs act like a regressive tax on the world's poorest workers, and despite the 2030 Sustainable Development Goal to reduce global remittance costs to 3%, fees have continued to increase by an average of 3.2% annually.

Among the major remittance channels, banks remain the most expensive, with an average cost of 12% in the fourth quarter of 2023. Post offices are next at 7.7%, followed by money transfer operators at an average of 5.5%, and mobile money services at the lowest at 4.4%. Although mobile operators have the lowest costs, they account for less than 1% of total remittance volume. In addition to high costs, traditional remittance methods often involve delays. Recipients may have to wait 2-5 business days for funds to clear as payments pass through multiple correspondent banks. Hidden fees and unfavorable exchange rate markups along the way further reduce the final amount received.

Stablecoins for remittances

Stablecoins and the cryptocurrency rails they run on offer an internet-native alternative, optimizing for speed, transparency, and low costs. Just as the internet revolutionized the global transfer of information by enabling instantaneous movement of information, stablecoins are similarly transforming the transfer of value. Because they run on public blockchains, transactions settle within seconds and are available 24/7.

While the average global remittance fee is 6.4%, on-chain transaction costs are often measured in cents or even fractions of a cent, thanks to recent advances in blockchain scalability. For example, Base's average transfer fee over the past two weeks was just $0.00024, compared to $0.155 on Ethereum. High-throughput blockchains like Solana and the upcoming Plasma blockchain, which aims to achieve zero-fee USDT transactions, are expected to further reduce costs.

Furthermore, the entire payment path is visible on the blockchain. No banking relationship or pre-existing account is required: Anyone with an internet connection and a digital wallet can send or receive stablecoins, providing access in regions with limited or underdeveloped banking infrastructure. Senders can deposit USDC or USDT via debit card or bank transfer, transfer these tokens almost instantly across borders, and exchange them for local currency through a network of local partners. Even factoring in withdrawal fees (now often as low as 0-2% on competitive gateways), the total cost is typically less than 2% of the transaction. This reduction in time and cost is a significant improvement for families who rely on remittances for their livelihoods.

Payment

While remittances represent a distinct subsector, the broader global payments ecosystem—spanning consumer transactions, money flows for businesses, public sector and social spending, and emerging embedded rails—continues to struggle with the limitations of legacy infrastructure. Core limitations include high costs, slow settlement times, low transparency, and poor composability. Despite these structural inefficiencies, the global payments industry remains one of the world's largest, processing 3.4 trillion transactions in 2023, representing $1.8 quadrillion in value and generating $2.4 trillion in revenue.

By taking a brief look at the most commonly used payment rails today, we can begin to understand how stablecoin and crypto rails can reduce fees and settlement times, thereby improving profitability and operational efficiency for businesses around the world:

Card networks: Card networks and payment cards originated with the launch of the Diners Club credit card in 1950 and have since expanded to process over $40 trillion in transactions annually worldwide. The card payment system is a multi-party network connecting four core participants: cardholders, merchants, issuing banks (which provide and authorize cards), and acquiring banks (which settle funds on behalf of merchants). These participants interact through either open-loop schemes (Visa, Mastercard) or closed-loop networks (American Express). When a consumer makes a payment, data flows from the merchant gateway (which encrypts and routes the information) to the payment processor, then through the card network to the issuing bank for authorization. Once approved, the funds are captured and ultimately settled in a batch cycle. The fee structure—interchange fees charged by the issuing bank, scheme fees by the network, and settlement fees by the acquiring bank—is set by the card network and varies by region and card type, ranging from 2-3% of the transaction plus a fixed fee (approximately $0.30). Modern payment facilitators (PayFacs) and orchestration platforms simplify merchant onboarding and optimize routing, increasing acceptance rates and reducing costs.

ACH (Automated Clearing House): ACH is the foundational payments network in the United States, moving trillions of dollars annually between over 10,000 financial institutions. Originally developed in the 1970s to replace paper checks, ACH gained national adoption when the federal government used it for Social Security payments. Today, it supports everything from direct deposits and utility bills to corporate vendor payments. The system processes both credit ("push") and debit ("pull") transfers, operating in batches rather than in real time. Each transaction involves the originator, its bank (the "ODFI"), an operator (such as the Federal Reserve or a clearing house), and a receiving bank (the "RDFI"). The originating bank bears responsibility for the legitimacy of the transaction, particularly in debit transactions—hence the 60-day consumer dispute window. Same-day ACH, introduced in 2015, allows for faster processing, but still faces limitations such as transaction limits and a lack of international coverage. Despite its age, ACH remains deeply ingrained in the US financial infrastructure due to its reliability, ubiquity, and low cost (US$0.21-1.50) compared to card networks.

Wire transfers: Wire transfers are the backbone of high-value, time-sensitive payments in the United States, primarily facilitated through two systems: Fedwire and CHIPS. Fedwire, operated by the Federal Reserve, uses real-time gross settlement (RTGS) to process transactions instantly, making it crucial for securities settlement and large corporate transactions. CHIPS, owned by major US banks and operated by clearing houses, serves a smaller number of institutions, reducing liquidity requirements through net settlement, with most transfers settled within the same day. Wire transfers are generally irreversible once sent, making them a reliable rail for final settlement. For international wire transfers, banks typically rely on SWIFT, a secure global messaging network used by over 11,000 financial institutions to transmit instructions rather than direct funds. Cross-border payments supported by SWIFT typically settle within one business day, but this depends on the chain of correspondent banks. Together, these two systems move trillions of dollars daily, underpinning the global payments infrastructure.

Payment Apps: Peer-to-peer payment apps such as Venmo and PayPal allow individuals to digitally send and receive money within a closed network, requiring users to create an account and log in to conduct transactions. These platforms offer a seamless, low-friction user experience in developed markets, typically allowing free personal transfers through linked bank accounts or balances, with settlement times of instant or less than a day. However, cross-border payments are more complex and involve additional fees, currency conversion, and regulatory friction. While peer-to-peer transfers may be free, business-related transactions typically incur fees of around 3%, making them attractive for personal use but costly for merchants or commercial transactions.

While the banking experience in the United States is seamless, in countries like Venezuela where inflation is high and trust in the banking system is low, stablecoins offer users a way to transfer value securely.

A16Z provides a comprehensive overview of traditional payment methods, detailing associated fees, settlement times, and operational details. Compared to crypto rails, these traditional systems appear outdated—characterized by high transaction costs, slow settlement, return risks, closed networks, and limited accessibility.

Merchants and Enterprises

In our view, stablecoin-based payments will have the most direct impact on US businesses, particularly those targeting the world’s largest consumer market, primarily due to the high rate of credit card usage and associated processing fees in the US.

A16Z provides a compelling case study highlighting the profit potential of integrating stablecoin payment infrastructure into large U.S. businesses. By reducing payment processing fees to 0.1%, the boost to profitability is significant:

Walmart, which reported revenue of $648 billion in fiscal 2024, is likely to pay about $10 billion in credit card fees, on net income of $15.5 billion. Eliminating these fees could boost profits by more than 60%, significantly increasing its valuation.

Chipotle: $9.8 billion in revenue, $1.2 billion in net income, and approximately $148 million in credit card fees. Reducing these fees would boost profits by 12%—an increase no other item on the income statement can match.

Kroger: Operating on a profit margin of less than 2%, it likely pays card fees comparable to its net revenue. For a low-margin retailer like Kroger, stablecoin payments could potentially double profitability.

In short, for large US companies facing significant drag from payment processing costs, crypto-native rails – and stablecoins in particular – offer an underutilized opportunity to unlock profit margins and boost enterprise value.